Walking is as close to a magic cure as there can be for better health, argues David H. Freedman in his compelling Politico article on making the suburbs more walkable. And indeed, the New York region’s high walkability, anchored in a robust transit network, is one of its most important health benefits, as we reported in the State of the Region’s Health.

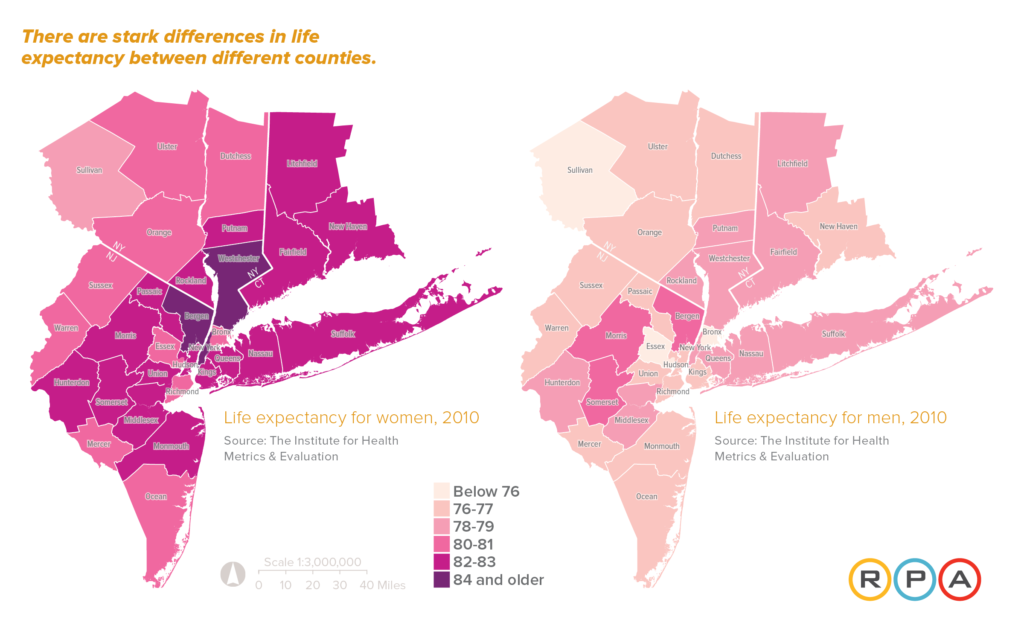

But if that’s the case, why is it that some of our most walkable communities also have the lowest life expectancy? Take a look at Northern New Jersey, for example. Life expectancy in Essex County, for both men and women, is far lower than in neighboring Morris County.

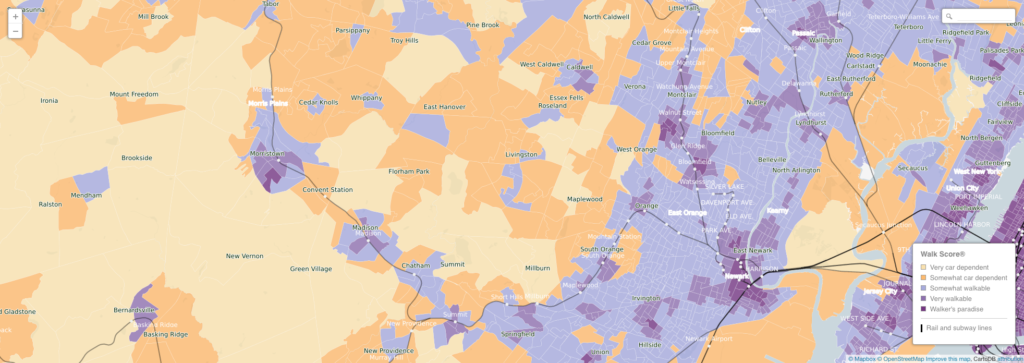

This is despite the fact that Essex County is overall far more walkable than Morris County.

Why the discrepancy? As documented in our recent report, 80% of a community’s health outcomes depends on place-based conditions, but neighborhood design that promotes walking or access to exercise opportunities is only one part of how where you live affects your health. Some of the most walkable places in our region are also those which have seen decades of discriminatory policies and disinvestment that have resulted in lower access to opportunity.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the quality of our public schools. A child growing up in Morris County will be far more likely to go to a high performing public school than one growing up in Essex County. And education can have a huge impact on public health. In the United States, people with college degrees on average live at least five years longer than those without a high school degree.

Our approach to using planning and design to improve the health (urban or suburban) has to be as diverse as the ways that the health of those communities is shaped by the built environment. We need to create more walkable communities, but we also need to expand opportunities more broadly. Walkability is only one piece of the puzzle.

Photo: Thomas De Los Santos