On May 27, 1929, over the crackling airwaves of NBC Radio, George McAneny presented to the public for the first time the Regional Plan for New York and its Environs. Otherwise known as the first regional plan of the Regional Plan Association, this document proposed creating an elaborate network of transit corridors and residential, commercial and industrial centers to provide access to more of the region and give options for living beyond the overcrowded core. Regional planning represented a new way of thinking, and the civic leader McAneny was at its forefront. By 1930, he would become RPA’s first president.

Today, New York City’s skyline, neighborhoods and urban systems are constantly evolving and becoming more complex, so it’s difficult to imagine a time when the foundational principles of zoning, planning, and preservation did not guide this growth. Yet the man who first created these frameworks for modern day New York - George McAneny - receives little recognition for his work. McAneny (1869-1953) built these frameworks while serving in numerous official positions, including New York City Comptroller, Manhattan Borough President, Executive Manager of The New York Times, and first president of Regional Plan Association. He was recognized locally and even nationally as a good government advocate and reformer who stood up to New York City’s corrupt political machine, Tammany Hall. Over the course of his career, this overlooked visionary fundamentally shaped this great city.

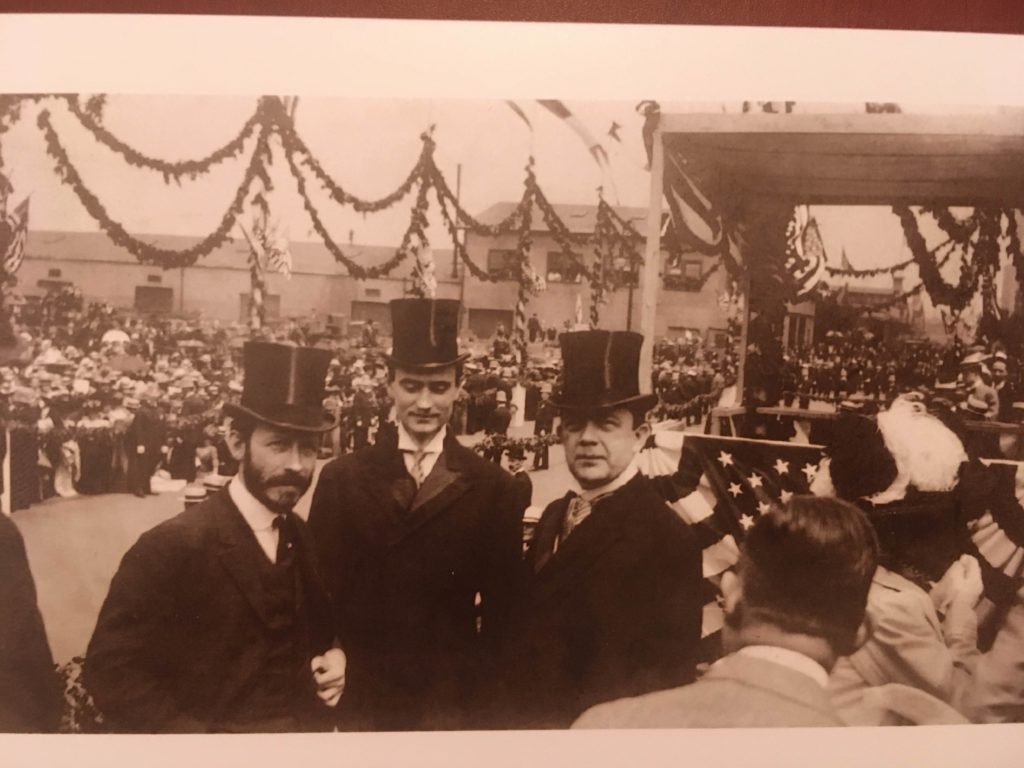

McAneny (left), a Democrat, was elected as Manhattan Borough President in 1910 as part of a fusion ticket with Republican John P. Mitchel (center) as the President of the Board of Aldermen, sweeping Tammany Hall (temporarily) out of power (Courtesy of Kay Ciganovic)

As President of the NYC Board of Aldermen, McAneny helped craft the 1916 Zoning Resolution, the first city-wide zoning code in the United States. At the time, planning primarily dealt with the aesthetics and physical perception of the city, as described by the prominent City Beautiful movement. Zoning gave planners much more impactful and practical tools. McAneny’s comprehensive zoning resolution, and later his leadership at Regional Plan Association, set the pace for local governments across the world, pushing other municipalities to develop zoning and planning boards. By providing local governments with the proper tools and resources to develop zoning commissions, McAneny helped to make communities more livable.

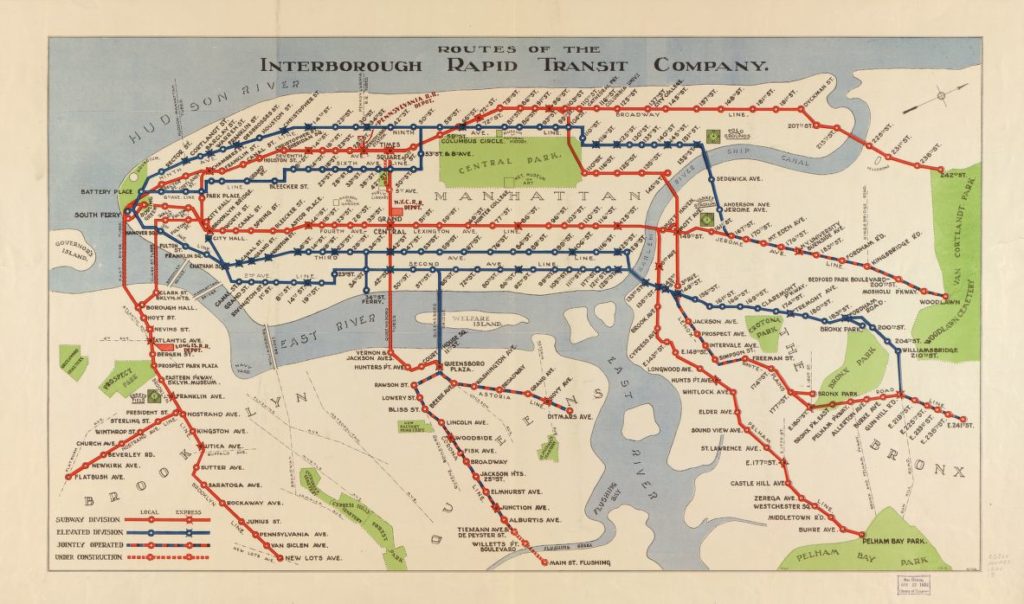

McAneny started his political career in the private sector as a lobbyist for the Pennsylvania Railroad during the creation of Penn Station. This experience would later help McAneny achieve one of his greatest planning accomplishments - creating a “Dual Contract System” in New York City. McAneny played a critical role in this negotiation between Interborough Rapid Transit Company and the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company. This partnership increased Manhattan’s midtown and downtown transit options, allowing for more one-seat rides, and brought subway lines further than ever before into the outer boroughs. This expansion, combined with McAneny’s new zoning innovations, enabled transit-oriented development to occur in previously underserved areas. Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx became immediately more accessible, decreasing congestion in the central business districts.

McAneny negotiated the signing of the “Dual Contracts” between Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) and Brooklyn Manhattan Transit (BMT). Both companies then expanded subway lines (red), elevated lines (blue), and elevated subway lines (blue and red) farther into the outer boroughs than ever before. (Courtesy of Library of Congress Geography & Map Division)

McAneny’s innovations did not always lead to positive change. Although he helped develop tools to more effectively plan communities, those tools were often used to create more segregated, less equitable communities. While McAneny preserved the aesthetic beauty of City Hall by moving a to-be-constructed courthouse, the courthouse would instead be built by clearing slums further north in Foley Square. As borough president, his implementation of street widening throughout Manhattan for transportation purposes led to the destruction of St. John’s Chapel on Varick Street. While McAneny may not have intended for these consequences, they are part of his legacy, too.

McAneny was also a preservationist. Side by side with RPA, McAneny fought Robert Moses on the proposed destruction of the landmark Castle Clinton in one of the most famous, protracted preservation battles in city history. Moses originally planned to erase Castle Clinton off the map to make way for his massive Brooklyn-Battery Bridge. McAneny and other preservationists worked tirelessly to have Castle Clinton designated a national historic monument, keeping it safe from demolition.

Today, 150 years since he was born, McAneny’s legacy extends much further than these specific projects. He spread the gospel of regional planning, and created a culture of preservation which still thrives today, making him one of the most remarkable and unsung of New York City’s visionary urbanists.

Please visit the new website www.GeorgeMcAneny.com, created by the Friends of McAneny Group, and check out the New York Preservation Archive Project’s Instagram account @nypap_org to learn more about McAneny.