RPA President Tom Wright gave this keynote address at Governor Cuomo’s Long Island Conference on Sustainable Development & Collaborative Governance on September 21, 2016 at the Hilton Long Island.

The twin themes of today’s conference—sustainability and collaboration—are always timely. But as I’ll describe in a moment, these are particularly urgent priorities in era of increasing global competition and accelerating global warming. I want to build on this morning’s discussion to frame the long-term context and challenges that we’ll need to address to attain a sustainable future.

“Sustainability” was once described as the concept that launched a thousand conferences. So I’m not going to try to define it here. But I think that at its core it means creating an inclusive prosperity, one that improves opportunity and quality of life for both current and future generations, and for all ages, races, ethnicities and incomes.

At Regional Plan Association, we have been promoting sustainability and collaboration across the New York metropolitan region for more than 90 years. For those of you who don’t know us, we are a non-profit Research, Planning and Advocacy organization that focuses on the long-term future for a region of 23 million people that extends across three states and includes Long Island, New York City, the Hudson Valley, northern New Jersey and southwestern Connecticut.

We cover most of the issues being discussed here today, from housing and economic development to transportation, energy and the environment. The heart of our work revolves around the creation and implementation of strategic plans for the region. We put out a new plan about once every generation, and will be coming out with our fourth regional plan next year. While these are strictly non-governmental and advisory, they have had a major impact on the development of Long Island and the region as a whole.

The first plan, issued in 1929, laid out much of the infrastructure that was built before and after World War II, including major highways like the Northern and Southern State Parkways and the preservation of open space that led to new parks, such as Jones Beach.

The second plan, released in the 1968, was in many ways a reaction to the urban sprawl and white flight of the 1950s and 60s, and proposed a number of regional centers to act as economic anchors outside of Manhattan, such as Mineola, and a regional authority to save the bankrupt commuter railroads.

In 1996, the third plan jumpstarted a new wave of transit projects, including East Side Access connecting the Long Island Rail Road to Grand Central Terminal, and proposed eleven regional preserves, including the Long Island Pine Barrens.

Today, we are in a much different place than we were twenty years ago. The region had gone through its worst economic decline since the great depression, with job losses that were greater than those of the 2008-2009 recession. Crime was rampant, and optimism was low. Now, we are one of leading metropolitan economies in the world. Our health and quality of life has improved by many measures, and we are attracting business and people from around the globe.

Yet our success is fragile and far from complete. Incomes have stagnated for all but the wealthiest households. Rising costs have made the region increasingly unaffordable. Our housing, transportation and other infrastructure are straining to meet demand. And climate change, just a footnote when we completed our last plan, is an existential challenge that impacts every development decision we make.

Nassau and Suffolk have also changed dramatically over this period, and it’s important to note that a new Island is starting to emerge. While Long Island will remain a suburban landscape of predominantly single-family neighborhoods, both its physical and demographic character are becoming more diverse.

Some of Long Island’s transformation has been going on for decades. We all know that the era of suburban sprawl is over, with almost no land left for new subdivisions. So any new housing or commercial development will have to come in existing downtowns, commercial strips or redeveloped industrial areas, shopping malls or office parks.

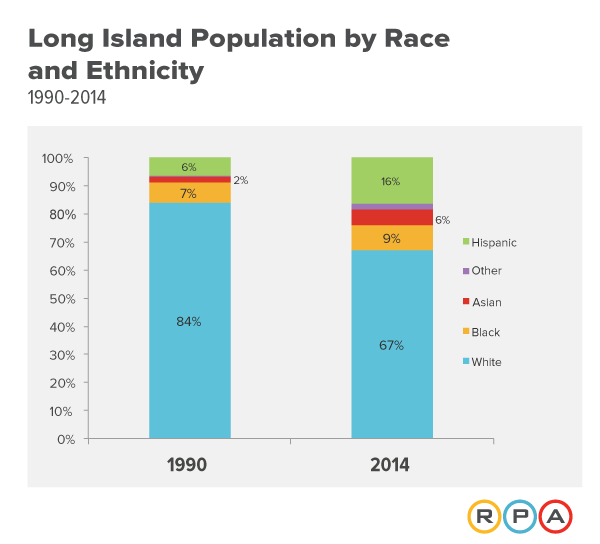

And new development will house a population that is becoming much more diverse. In 1990, only 16% Long Island’s population was black, Hispanic, Asian or Native American. Today, these account for a third of everyone who lives in Nassau and Suffolk. And with younger age groups much more diverse than those over 40, it’s guaranteed that this trend will continue. By 2040, it is likely that nonwhites will be a majority of Long Island’s population.

And just like everywhere else, the aging of our population that is already underway will accelerate as baby boomers enter their 60s, 70s and 80s, reshaping everything from healthcare to housing and transportation. In fact, most of the Island’s population growth over the next 25 years will come from those 65 and over.

But more recent changes are also underway.

It took a few years for Long Island to emerge from recession following the 2008 financial crisis, but Long Island is now starting to build again. The new projects are not the office parks or single-family homes of previous years. Instead, these are multifamily and mixed-use projects, mostly in or near existing downtowns.

An inventory conducted by the Rauch Foundation’s Long Island Index found 26,000 units of multifamily housing either under construction or in the pipeline. This reflects the large unmet demand from both Millennials and empty nesters looking for similar types of housing. But it is also a tribute to the perseverance of far-sighted elected officials, community leaders and business executives to work through the complex process of consensus-building, financing and obtaining approvals.

Just as important, new investments in infrastructure are underway. In particular, the Long Island Rail Road will be vastly improved a decade from now. Commuters will be able to travel directly into Grand Central Terminal as well as Penn Station, shaving commuting times substantially for many and helping to relieve congested highways. A second track on the Ronkonkoma line will provide more frequent and reliable service on the railroad’s fastest growing and most overcrowded line.

And Governor Cuomo’s breakthrough proposal for building a third track on the LIRR’s main line will provide greater reliability for the entire system, increase capacity and convenience of reverse commutes – which are the fastest growing portions of the MetroNorth and NJtransit systems – and open new possibilities for traveling within Nassau and Suffolk, and not just to and from Manhattan.

As hopeful as some of these changes are, they are not enough to address the scale of the challenges that we face. Greater diversity can strengthen Long Island economically and socially, but only if we can overcome a history of segregation in our neighborhoods and schools. The upturn in multifamily housing is welcome, but much more needs to be done to meet Long Island’s needs for more affordable housing at all income levels. Improvements in the LIRR are critical, but they won’t solve the need for more north-south mobility, adapting to driverless cars, or using technology to make it easier to get to the places where transit can’t go.

And all of these issues require more proactive and concerted effort to address the ways that climate change will affect all of us. To build on efforts already underway, I’d like to propose four considerations that need to be part of any strategy for a more sustainable future:

- Long Island’s future is inexorably tied to the future of New York City and the entire tri-state region.

- Climate change is forcing us to redefine the whole concept of sustainability.

- We need to reconnect growth to broadly shared prosperity and opportunity.

- If we are to have any hope of addressing these challenges, we need to change our institutional and governance processes.

Long Island and New York City are mutually dependent and need to collaborate with each other and the rest of the tri-state region to address shared problems.

We share the same environmental assets, such as the Long Island Sound, a shared ocean coastline, and the air that is affected by building and auto emissions from throughout the region. Energy-providing natural gas moves in pipelines from wells in Pennsylvania, across New Jersey and New York City to power plants on Long Island.

Long’s Island’s prosperity depends on the dynamic economic engine in Manhattan. 30% of Nassau’s workforce and 11% of Suffolk’s work in New York City, and bring home $26 billion dollars in wages that are recycled through Long Island’s economy. But neither could New York City’s economy exist without the housing and high-skill workforce provided by Nassau and Suffolk counties.

The potential for improving these flows, to the benefit of everyone, is substantial. From 1990-2010, nearly all of the net increase in commutation into Manhattan was from west of the Hudson River, where more housing was being built and where improvements in New Jersey Transit gave more people a one-seat ride to work. The improvements underway on the Long Island Rail Road, if combined with more housing near the stations, could give Long Island the same advantage.

And the need to collaborate is borne out by two recent trends. Over the last decade, jobs have grown more than three times as fast in NYC than they have on Long Island. Over this same period, housing costs have risen dramatically throughout the region as the demand for housing has dramatically outstripped supply. New York City can’t produce enough housing on its own to keep its economy going, and the best way for Long Island to generate more high-paying jobs is to look for ways to serve growing regional industries, from technology to tourism, that are now expanding mostly within NYC’s five boroughs.

Business leaders have long known this, but government is increasingly getting into the act. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, for example, has recently created an office of regional planning to work with other municipalities throughout the region on common challenges.

More than anything else, the future will depend on how we respond to climate change. In fact, it is forcing us to redefine the whole concept of sustainability. Sustainability has traditionally emphasized preserving and nurturing the environment that we have. But the environment that we have now is not the one that we will have 25, 50 or 100 years from now.

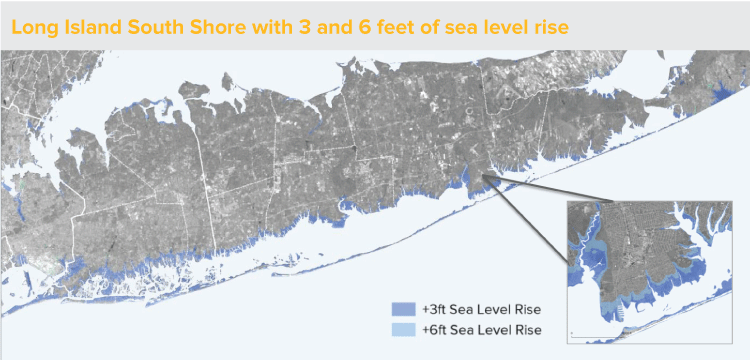

Climate change is already here, is generating more extreme temperatures and is increasing the frequency and intensity of storms. By 2050, nearly 250,000 Long Island residents are likely to live in places vulnerable to frequent flooding from tides and storms.

Scientists tell us that we could see three feet of sea level rise in the second half of this century, and six feet as early as 2100. At six feet, neighborhoods that now house approximately 200,000 residents would be permanently under water, including much of Long Island’s south shore from Long Beach to Mastic Beach and beyond. And much of the region’s most critical infrastructure, from our airports to our power system, would also be affected.

So preserving the status quo is no longer an option. As we adapt, can we improve communities and quality of life? Where we need to build dunes, berms and barriers, can we expand our parks and economy? Where we need to move back, can we create neighborhoods that are even better than the ones we had previously? And can we give our most vulnerable residents the resources to choose where and when to live?

A sustainable future also requires reconnecting the need for growth to broadly shared prosperity and opportunity. “Growth” has become a dirty word, not just on Long Island but throughout the region and, indeed, in much of the nation. The age when growth was associated with rising incomes and upward mobility is long past. Now, growth is associated with congestion, displacement and higher costs. And it’s not surprising that this is the case. Until recently, average incomes hadn’t risen since the 1990s. When new housing is built, it often costs more than most local residents can afford.

How do we square this with the fact Long Island and the region has a massive housing shortage that will keep prices high unless we build enough to meet demand? By our estimates, we need to increase housing production in the region by 50% to keep up with a growing population and start to bring costs down. And we can’t do this unless more housing at all income levels—low, moderate and middle-income especially – is built in all parts of the region: on Long Island, in New York City, in Westchester, New Jersey and Connecticut.

Without growth, we also won’t be able to provide enough job opportunities to lift people out of poverty or raise incomes for average households. A growing economy doesn’t guarantee that poverty will fall or incomes will rise. We’re still fighting an uphill battle against globalization and technological change that drives inequality higher. But we have a far better chance to make progress if we’re creating jobs than if we’re shedding them.

And what about traffic congestion, public health, clean energy and water quality? We have to be honest about how new development will affect these, both locally and regionally. But with an engaged community and good design, those issues can be addressed. And unless we’re expanding our tax base, we won’t have the resources to fix the problems that we have now.

You can explore these issues in greater depth in the report RPA issued earlier this summer, Charting a New Course, that fleshes out the implications for different development paths for the region. The report emphasizes that how we grow matters as much as how much we grow. The essential principles are well-established:

- Engage communities early and empower them in the decision-making process.

- Focus development in existing downtowns and corridors that can support additional growth.

- Provide affordable housing and other benefits for both existing and new residents.

- Incorporate high-quality design to improve the visual and functional aspects of new development.

Yet even if we adhere to these principles, resistance will still be fierce and progress will be slow. If we are to have any hope of meeting these challenges, we need to change our institutional and governance practices.

Development proposals take far longer to reach a decision on Long Island than elsewhere in the region, discouraging good projects, increasing the cost of development, and making it harder to provide affordable housing. Communities need to get meaningful resident engagement in the planning process while providing a speedier process and a greater level of certainty for developers.

The state can also play a stronger role to provide incentives for sustainable development. Massachusetts reimburses towns and villages for additional costs resulting from mixed-income, multi-family development. California requires regions to produce combined housing and transportation plans to both reduce carbon emissions and provide their share of the state’s affordable housing needs. Many states have regional or county school districts to improve education opportunities for low-income and minority students.

These are the types of reforms that we will need to take seriously if we are to address the scale of the challenges that we face.Today’s conference is a step in the right direction, especially with all the stakeholders and decision-makers assembled. Thank you for the opportunity to share RPA’s research and proposals. We look forward to working with Governor Cuomo, local officials, The Long Island Regional Economic Development Council, and all of the stakeholders participating today to further the progress that has already been made.

Photo Credit: Dune Road, Long Island by Peter Dutton // Flickr