Sasha Blair-Goldensohn’s powerful first-person account in the New York Times reminds us that the New York City subway system’s biggest outrage isn’t overcrowding or delays, but the lack of accessibility for wheelchair users and others with limited mobility. This glaring lapse in public service can wreak havoc with the lives of the disabled, who are more likely to be poor, and the elderly, and inconveniences many others wheeling strollers or luggage. Blair-Goldensohn vividly describes what it’s like to get on the subway at one station thanks to an elevator, only to be stranded on the platform when he discovers that the elevator at the end of his trip is out of service.

Fewer than one in four NYC subway stations have working elevators. A map created in 2015 by lawyer and transit enthusiast Matthew Ahn shows how sparse the network becomes for passengers dependent on elevators. Even when stations are technically accessible, the system’s severe crowding makes it very difficult for the disabled to navigate platforms and trains.

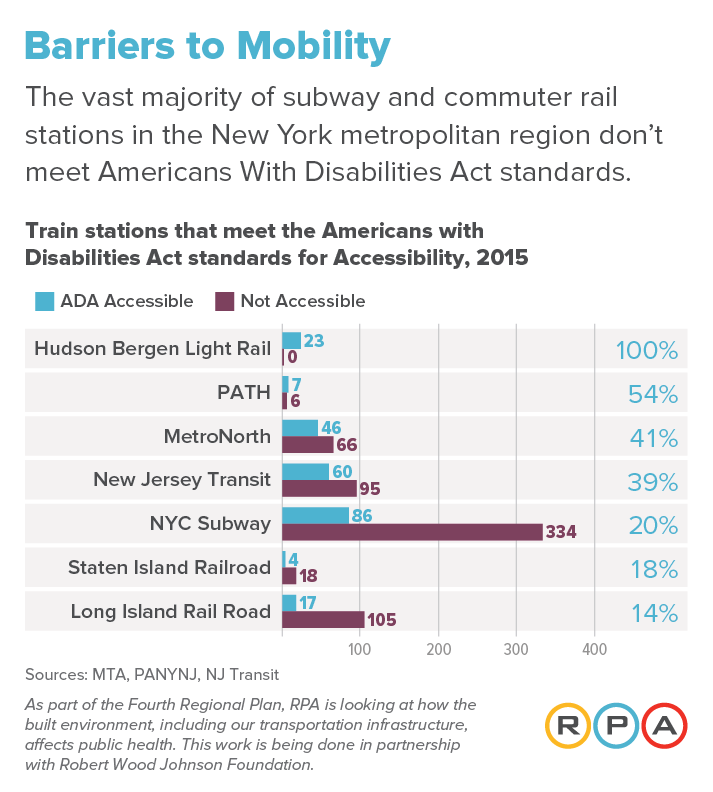

The problem isn’t confined to the subway network. In a study last year on the region’s health, Regional Plan Association found that nearly all of the metropolitan region’s rail systems had large numbers of inaccessible stations. The lowest ADA-accessible share was the Long Island Rail Road, at 14%. One bright spot: The newest line, the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail, is 100%-accessible.

It’s of course easier to incorporate elevators and other accessibility features when you’re starting from scratch. The MTA has invested heavily to make its bus fleet more accessible, and the MTA and other agencies have made slow progress in rehabilitating old stations to make them compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. The improvements are costly, and the region’s transit agencies are perennially underfunded. But that’s small comfort to passengers who need to use mass transit to get around.

Photo: Gene Han