2018, another tumultuous year in national and global politics, marks the eighth consecutive year of strong economic growth in the tri-state New York region. Since employment bottomed out following the 2007-2009 global financial crisis, the region has added an unprecedented 1.3 million jobs along with 730,000 people. This long expansion has also changed the shape of the region, pulling more people and jobs towards the urban core, putting strains on housing and infrastructure and leaving many smaller cities and far-flung suburban and rural towns with stagnant economies. Unemployment and poverty have declined, but average incomes have been slow to rise.

2019 could be a pivotal year. Just as the benefits of a growing economy were starting to reach low-wage workers, warning signs are flashing that the New York region’s remarkable expansion is likely to slow, and could even stall, in 2019. While most economists expect New York to continue adding jobs, declines in the stock and bond markets could pull down the financial industry. The national economy is likely to slow. Congestion and crumbling infrastructure, from the subways to NYCHA, are getting worse.

Regional Plan Association has updated many of the trends highlighted in its 2017 Fourth Regional Plan. This brief snapshot of the changes to New York City, northern New Jersey, southwestern Connecticut, Long Island and the Mid-Hudson Valley can be found here. Here are five of the most important trends that will determine in 2019 is a boom or a bust.

1. Growth in technology and tourism should make the region’s economy more resilient, but the risks from declining financial markets and a national slowdown are still high.

New York’s boom and bust cycle has long been ruled by the ups and downs of the financial markets that drive an outsized proportion of the region’s output, wages and tax revenues. While still critically important to the New York region’s economy, the finance industry was joined by technology and tourism as drivers of the recent expansion. Technology, from large firms like Google and Amazon to small information technology entrepreneurs, is one of the fastest growing sectors and, according to Cushman & Wakefield, accounts for nearly 500,000 jobs in the New York area. And unlike prior expansions, the region has actually outperformed the nation as a whole.

This more diversified economy is likely to be put to the test in 2019. Stock, bond and commodities markets have all taken a beating at the end of 2018, and many analysts are predicting the end of the second longest bull market in U.S. history. Trade worries, rising interest rates and the end of the fiscal stimulus injected by the 2017 tax and spending legislation have many economists expecting a marked slowdown in the U.S. economy, if not an outright recession. In past cycles, the combination of a slow U.S. economy and a declining stock market resulted in steeper and longer declines in the region than in the nation as whole. In theory, the region should do better when the next finance-led slowdown or recession comes to pass. But technology and tourism can also be volatile, and it remains to be seen how well New York will withstand a year or more of turbulence.

2. New Jersey, Long Island and the Hudson Valley have started to catch up to New York City’s job growth, and growth rates are likely to converge further.

Jobs have grown more than twice as fast in New York City as they have in the rest of the 31-county region since 2010. That reflects both the remarkable pull of talent and high-value services toward New York and other major cities worldwide, and declining investment in new housing and infrastructure outside of the five boroughs. And it’s not just job growth that has been out of balance. Population grew by 6% in New York City and Hudson County, by 3% in the inner suburban counties and less than 1% in the outer suburbs. And housing prices actually declined since 2010 in most outer ring counties while they soared by over 50% in Brooklyn and Manhattan.

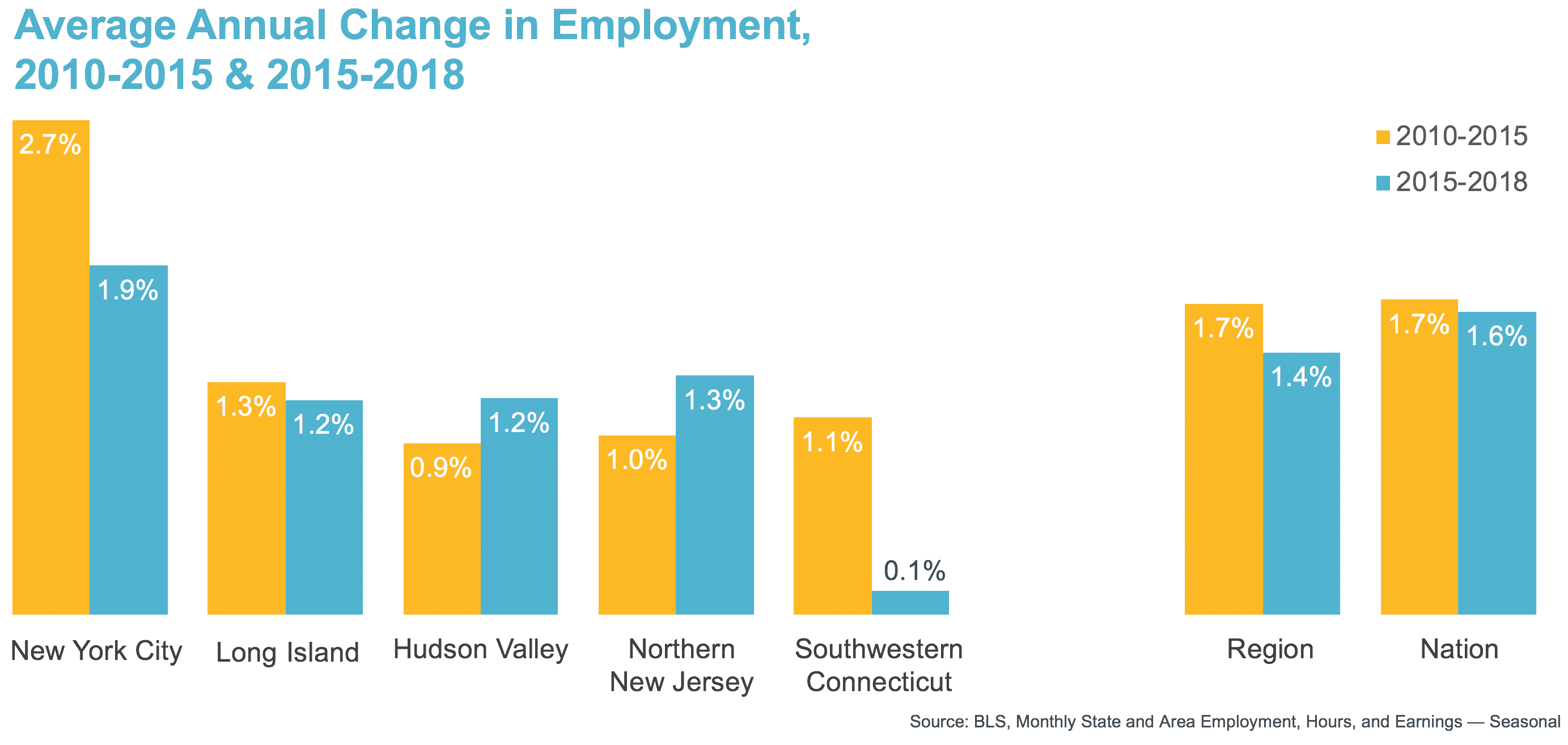

In the last three years, however, growth rates have started to converge, mostly because New York City slowed from its torrid pace in the first half of the decade. While the city’s annual rate of job growth slowed from 2.7% in 2010-2015 to 1.9% in 2015-2018, New Jersey, Long Island and the Mid-Hudson Valley either maintained or increased their rate of growth to about 1.3%. Connecticut was the outlier, falling from 1.1% to only 0.1% in the last three years. Growth rates should continue to converge in the short term as the city becomes more expensive and momentum picks up in other parts of the region. Whether this can be maintained will depend on whether smaller cities and towns expand the number of homes available at all income levels and whether transportation improvements better connect these places to existing job centers.

3. Economic growth has not significantly lowered rent burdens, and improvement will depend on policy choices.

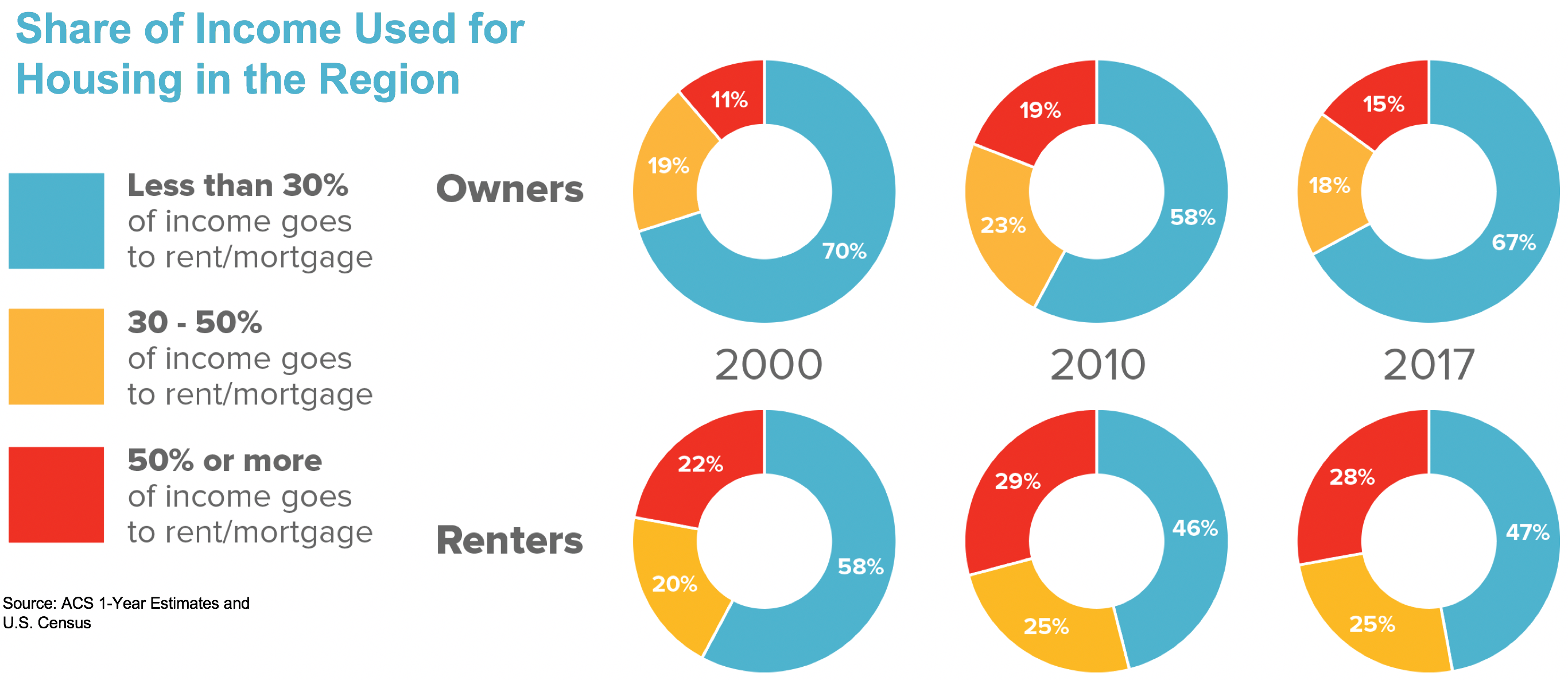

Sluggish wage growth and rising inequality have limited the benefits of the current expansion. With income gains concentrated at the top and mortgage rates tumbling, the share of income going to housing costs has declined substantially for home owners. But for renters, housing costs remain exceptionally high. Twenty-eight percent of renters pay more than half of their income for rent, and another 25% pay between 30 and 50 percent of their income. Both shares have barely budged since 2010 and are much higher than they were in 2000.

There are some reasons to hope that this could improve in 2019. Wage growth has picked up some and parts of the housing market have started to cool, which could reduce pressures on rents. But major uncertainties include the fate of rent regulation, particularly in New York City, and the pace of affordable housing construction throughout the region. Without both preserving and expanding the stock of low and moderate-income housing, even continued declines in unemployment and stronger wage growth will result at best in only modest gains in affordability.

4. Commuting times will continue to rise and transit ridership will continue to decline without improvements to transit network.

As the expansion wears on, growing congestion and a deteriorating transit system have made commutes longer, less reliable and more unpleasant. And that trend has worsened in the last 3-4 years. From 2010 to 2014, the share of people commuting over 60 minutes grew from 18.5% to 19.6%, and from 2014 to 2017 the share grew to 21.3%. And the increase was particularly striking in the urban core and inner suburbs. For Bronx commuters, for example, those traveling more than an hour increased from 34% to 38% from 2010 to 2017. In Westchester, the share increased from 18% to 22% and in Bergen County from 16% to 20%.

More commuters, tourists and other travelers overwhelmed subways, buses and commuter rails following years of underinvestment. As the system started to break down, and as more people started using alternative services such as Uber, Lyft or Via, transit ridership started to decline. A long-term decline in bus ridership accelerated, and subway ridership started to decline in 2015 after two decades of growth. New Jersey Transit ridership started to decline in 2016, while growth leveled off on Metro North and Long Island Rail Road. Streets became more crowded with traffic, making it harder to get to where you going whether you drove, took a train or bus, walked or biked. These trends will not be easy to turn around, but implementing congestion pricing for cars and trucks entering the Manhattan central business district provides the best opportunity in 2019 for both reducing traffic and generating revenue to invest in the transit network.

5. There has been little growth in renewable energy for power generation, but state initiatives for offshore wind, solar and other renewables could change this trajectory.

From hurricanes to wild fires, extreme weather events were common and destructive throughout the world in 2018. These events came amidst stark reports and increasingly urgent warnings on the accelerating pace of climate change and the need to sharply reduce greenhouse gas emissions from entities ranging from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to the National Climate Assessment. New York, New Jersey and Connecticut have all adopted aggressive goals for reducing greenhouse gases and expanding renewable energy. One key measure—sources of energy generated by power plants—shows a mixed picture. Since 2010, the region has made progress in reducing the generating capacity powered by oil and coal by 10% and 5%, respectively. Natural gas, which emits far fewer but still significant amounts of greenhouse gas, grew by 12% and accounts for most generating capacity. But solar and other renewables grew little and account for a very small portion.

Offshore wind is a particular focus of the states and has tremendous potential not only for supplying clean energy but for expanding jobs and economic activity. How rapidly and effectively the states, cities, counties and towns in the region expand their use of renewable energy could make a significant contribution to mitigating climate change in and of itself and provide models for other regions to follow.

View Presentation: A Brief Snapshot of Changes in the New York-New Jersey-Connecticut Region