Each time an autonomous vehicle company does a trial in a city it gets a huge buzz. And while cities with their higher population density might be the end goal for companies that provide AV technology, the larger need and the larger impact of AVs might lie outside the urban core.

So how can AV technology improve mobility in the suburbs?

The suburbs, in part due to their lower population density, have fewer public transit options and fewer options overall for those who do not or cannot drive. That’s a huge niche for AVs to fill. And it’s not just a public policy dream. Bloomberg & McKinsey estimate that 75% of AV sales in North America and Europe will be made in the suburbs. At first, much of those sales could be for private driverless cars, but AVs can also be shared and serve as the first-and-last mile public transportation option that many suburbs desperately need.

This week RPA released a new brief that suggests ways that urban and suburban policymakers can act now to begin to shape the streets and mobility policies needed to maximize the benefits of AV technology, while also navigating its possible risks. The brief suggests that when shared, electric and operated in a way that complements public transit, autonomous vehicles present great promise for mobility in the suburbs. The brief was developed as part of our research towards the Fourth Regional Plan that will be unveiled in full on November 30th.

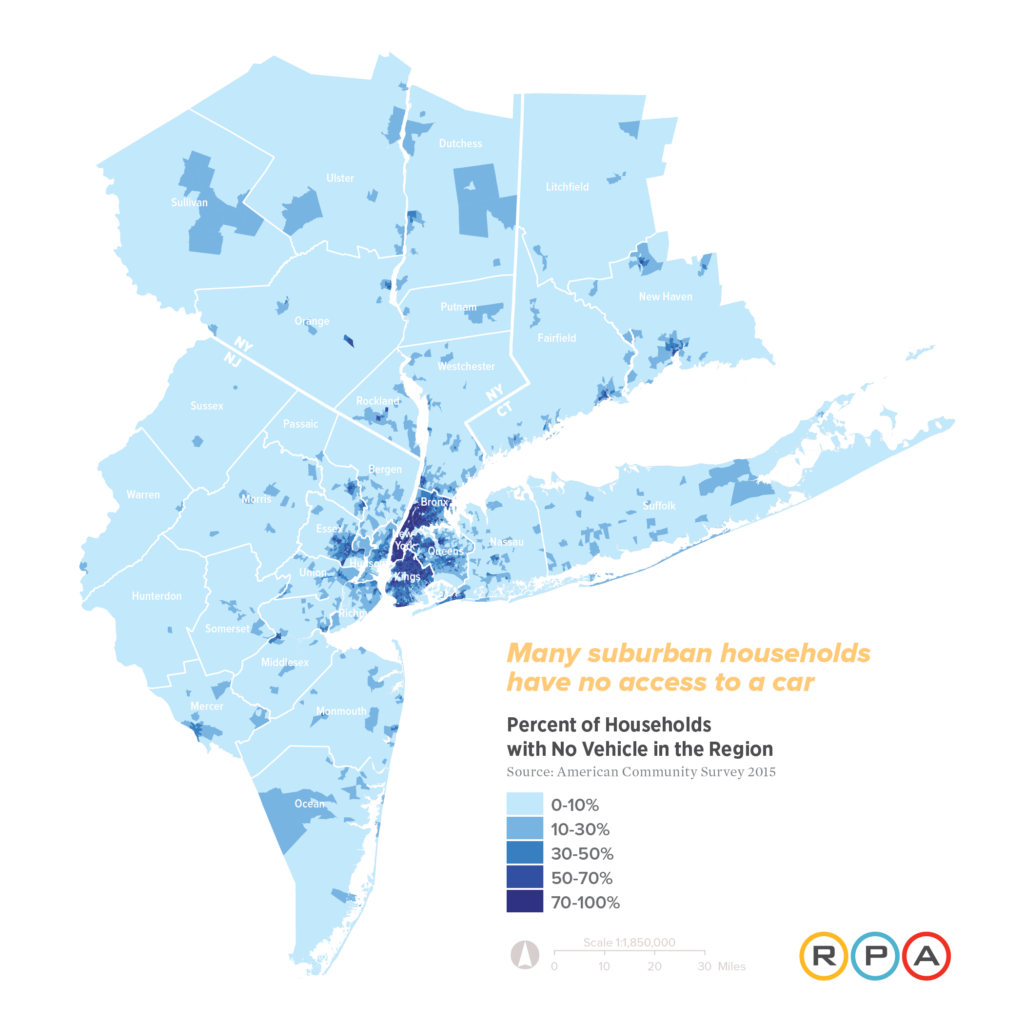

Local suburban transit agencies and state DOTs should focus on making AV services accessible to low-income, disabled, and elderly individuals. In the suburbs and rural areas, agencies often run bus lines at operational costs that average around $5 per rider but can cost upwards of $20 per rider - compared to NYC’s average of $3 per rider. They also struggle to provide frequent fixed route service due to these high costs and when they do, service is often infrequent and unpopular with riders. Yet, many suburban communities in the New York region have low-income populations with little access to private vehicles, making them reliant on these subpar transit services. AVs have the potential to supply more flexible and reliable service in these low-density areas at a lower cost to both agencies and consumers.

On-demand services provided by Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) foreshadow the shared ride model that AVs will ideally replicate, and some suburban transit agencies are already testing ways to incorporate these services to provide better service for constituents. Pinellas County, Florida, has received a federal grant to provide free on-demand rides for workers with late-night shifts. It has also cut two bus lines and replaced them with subsidized Uber services to bus stops on lines with more frequent service. Lyft ran a similar pilot in Centennial, Colorado. In the New York region, Summit, New Jersey has offered Uber ride subsidies to and from its train station.

There may be challenges in acquiring users that are accustomed to the comforts of personal vehicles, as experienced in Summit. In the suburbs, the personal vehicle serves as a locker to store a gym bag or games for children on the way home from school, and it allows trips with several stops for errands. But over time, attitudes toward shared travel may evolve or vehicle design may accommodate the need for a space to store personal items. And to those who currently rely on public transportation, on-demand services will bring increased flexibility. If suburban travelers fully embrace the shared transit economy, the New York region could reclaim over 7,000 acres of impervious parking surfaces around train stations for both public and private development – equivalent to about half of the area of Manhattan.

As AV technology becomes less expensive and private AVs become more appealing to the masses, we cannot repeat the mistakes of the automobile age. Long-haul trips by car will become leisure and work time, more like transit, which means residents will no longer jockey to live near a train station, potentially leading to an exodus from transit and an increase in suburban sprawl. To incentivize transit use and to free up valuable land that is today used as parking near train stations, transit agencies should prioritize subsidies for on-demand services in closer proximity to train stations. This subsidy may also extend to rural areas with no transit options.

As more vehicles become electric, the gas tax may be replaced by a vehicle-miles-traveled tax that will be easier to enforce with connected vehicles. Such a tax could also limit private AVs from traveling empty and incentivize denser development in the suburbs

Although there are great uncertainties that still exist around the exact timing and speed of AV adoption, one thing is clear. Adopting sensible policies today that promote transit, preserve walk- and bike-ability and provide more mobility options for those who do not and cannot drive is a no regrets move.

Photo: dllu/ Creative Commons