- Who uses the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway and how and why do they use it?

- How does the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway affect carbon emissions?

- How can the results of the study support the advocacy of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway, as well as other greenways?

- How can this study serve as a model for future studies?

In brief, the intention of the project team is to increase understanding of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway to build both community and political support for its improved design, completion, and maintenance as well as foster support for other greenways across New York City.

As presented in this study, the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway will be 29 miles when completed and extends along the borough’s entire waterfront through city streets and parklands. As of this report’s release, seven miles of the Greenway remain incomplete.

The study is based on creating entirely new data sets, and this report aggregates those findings. The research is based on three methods of data collection: field researchers conducting intercept interviews with over 1,000 greenway users; installation of sensors at 32 locations to count greenway use and mode of transportation; and a panel survey of residents in zip codes including the Greenway. Data collection was led by the study team with consultation from a technical advisory committee (listed in the appendix) comprising city agencies, elected officials, NGOs, mobility companies, and others.

Key Findings and Recommendations

New and important findings in this report answer the following questions, in some cases for the first time:

Thousands of people use the Greenway, but usage varies by location and time of year

Sensors counted an average high of 23,500 bicycles and 36,000 pedestrians per day during the peak month of July. The least active month (January 2024) included 7,400 cyclists and 16,500 pedestrians. Overall use was highest in Williamsburg/Greenpoint and lowest on Jamaica Bay Greenway among all sections.

For comparison, average daily ridership for NYC Ferry in 2022 was about 17,300 passengers.

Fewer cyclists were counted along sections of the Greenway that had not yet been completed.

People use the Greenway for recreation, exercise, and commuting to work in all kinds of weather

Along every section of the greenway, most people are using it for recreation, exercise, and meeting people. Along Shore Parkway and Jamaica Bay Greenway sections, the share is over 90%.

More than 23% of Greenway bike trips and 12% of all trips were for commuting (3,000-7,000 per day in spring and summer), and the highest rates were in Williamsburg/Greenpoint, Brooklyn Bridge Park, and Red Hook.

Users rely on the Greenway year round and in all kinds of weather. Poor weather conditions such as extreme cold, heat, rain, snow and wildfire smoke only reduce greenway usage by about 30% for pedestrians and 42% for cyclists.

Greenway user demographics reflect the surrounding neighborhoods

Overall, Greenway users are equally likely to be (self-identifying) men or women. However, when broken down by mode of transportation women represent the largest percentage of walkers and runners and men the largest percentage of cyclists.

For each section of Greenway, racial and ethnic demographics of users reflect the demographics of surrounding neighborhoods.

Of the greenway users who revealed their income to interviewers, greenway users were more likely to have incomes over $75,000 than surrounding communities.

The Greenway has the potential to facilitate transportation mode switches

Bike infrastructure like greenways encourages biking, and can facilitate long-term mode switches that include shifts away from car ownership, and one recent study estimates that bike trips in New York City between 2014-2017 saved 493 tons of CO2 citywide. That said, findings suggest that the carbon impact of day-to-day trip decisions is relatively low, as when asked how they would have made their trip if the Greenway didn’t exist, only 2% would have taken a car.

Users are connecting to ferries and subways — but not to buses

About 21% of trips on the Greenway will connect to transit, but 88% of users report use the greenway to connect to transit in general. DUMBO has the highest percentage of users connecting to transit (specifically, subway and ferry).

The Greenway provides important connections to ferry services in multiple communities. In Sunset Park, almost 20% of users were connecting to the ferry.

Destinations like Coney Island are well served by the subway system, but the greenway there planned on Neptune Avenue has not yet been built.

A very low percentage (less than 2%) of Greenway users were connecting to buses, perhaps reflecting the lack of cycling amenities on many city buses.

Awareness of the Greenway could be better

Awareness of the Greenway and its route could be significantly improved. Only about 60% of greenway users could identify they were using the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway.

In the online panel, 60% of respondents said they had not used the Greenway since they didn’t know where it was.

In addition to these questions and high level takeaways, we have broken the analysis down on a community level for 8 sections of the Greenway (both completed and proposed): Williamsburg/Greenpoint; Brooklyn Navy Yard/DUMBO; Brooklyn Bridge Park; Red Hook/Columbia Street; Sunset Park; Shore Parkway Greenway; Coney Island/Sheepshead Bay; Jamaica Bay Greenway.

Recommendations:

In response to the study findings and others, we have included high level recommendations to improve the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway including the following:

Complete the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway in the immediate short term

Follow through on the commitment to upgrade entry-level facilities

Prioritize the establishment of greenway-like alternatives around work zones

Improve design standards to meet tomorrow’s usage needs and prevent vehicle intrusion

Improve and standardize wayfinding for greenways

Upgrade connections to surrounding neighborhoods and increase the number of access points

Maximize connections to public transportation

The Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway User Study is a first-of-its-kind, data-driven analysis of one of the most heavily used and dynamic greenways in the United States. This study is important to advance improvement and completion of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway and is also relevant for greenway planning across New York City and in other North American cities.

We are releasing this study at an important time in greenway planning in New York City including completion in 2024 of the city’s first citywide greenways plan since 1993; planning of 60 new or upgraded miles of greenways over the next two years funded by a USDOT RAISE grant; implementation of NYC Parks Destination Greenways program; and other projects across the city. A complete greenway is a long, linear space that connects many communities and destinations and provides full protection for walkers, runners, cyclists, and other forms of micro-mobility from cars and trucks and space for trees and plants. Greenways provide a safe and often green corridor, physically separated from auto traffic by barriers or green space. Greenways are also intended to produce environmental benefits, hence the proximity to and inclusion of parks, trees, and other natural spaces along and within greenway routes.

The Greenway traverses a diverse range of communities in population and typology. In the densely developed neighborhoods of northern Brooklyn where the Greenway is built into the right of way of city streets and is easy to enter and exit as part of the street grid.

In southeastern Brooklyn, the greenway is fully located within a strip of parkland that is separated from nearby neighborhoods by highways, has fewer entry points, and is located beside the water. In other communities such as Red Hook, Sunset Park, and Coney Island, there are significant gaps in the Greenway network. The Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway encompasses the Shore Parkway Greenway and Jamaica Bay Greenway as well as sections designed in the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway Implementation Study, created by NYCDOT in 2012. According to city greenway planners, 22 miles of the 29 mile Greenway are “complete,” but in some locations the “complete” sections remain as “quick build” infrastructure (painted pavement; plastic sticks; etc) and are not protected by curbs and planting barriers – basic components of a fully developed greenway. As we describe in detail in this report, the design and location of the Greenway affects its relationship with surrounding communities and patterns of use.

This unique and innovative study was initiated by Brooklyn Greenway Initiative (BGI) in 2019. A non-profit started in 2004, BGI’s mission includes advocating for improvement and completion of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway and working with the NYC Greenways Coalition and city partners to plan, expand, and connect the city’s greenway network across all five boroughs. In organizing this study, BGI identified a need for more understanding of greenway usership and how a well-designed and maintained system can advance the city’s goals for mobility, recreation, health, safety, air quality, climate resilience, economic development, tourism, and social cohesion.

This study is the product of an innovative, cross-sectoral partnership. Since its beginning in 2004, BGI has worked closely with NYC Department of Transportation (NYCDOT), which oversees the city’s streets, and Regional Plan Association (RPA), a 100-year old nonprofit dedicated to economic health, environmental resiliency, and quality of life in the NYC metropolitan area. BGI developed and conducted the user study in partnership with NYCDOT and RPA and with Numina, which has developed computer vision sensors built for city streets. Further, the sensors were installed on NYCDOT light poles powered by Con Edison. The project leaders (BGI, RPA, Numina, and NYCDOT) also regularly met with the study’s technical advisory committee, which is listed in full in the appendix and is comprised of government partners (including NYC Parks; Economic Development Corporation; and Mayor’s Office); urban planning, mobility, and data nonprofits; and others.

User Study Purpose

In creating the User Study, the project leaders identified a need for improved understanding of the who, when, how, and where of greenway use. Other datasets have relied on counters embedded in pavement in bike lanes and hand counts. The User Study provides a more in-depth, community-level understanding of Greenway use and relies on three new datasets: intercept interviews by field researchers of over 1,000 greenway users; a panel survey of 330 Brooklyn residents living near the greenway; and 13 months of continuous counting of greenway users on foot or bike at dozens of locations. With this information, greenway planners and designers, advocates, and current and future users alike have a rich data set to know how the greenway is being utilized - such as for a delivery or commute to downtown Brooklyn or lower Manhattan or a lengthy, recreational run or bike ride along the New York Harbor and Jamaica Bay.

The project team sought to answer the following questions.

Who uses the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway, and how and why do they use it?

Distinct from existing data and studies, this technology-enabled study allowed us to collect data on how and why people use the Greenway along its entire length. Using a combination of emerging technologies and diligent field research, we sought a way to understand the comprehensive impact of the greenway on the lives of New Yorkers. We want to demonstrate how a well-designed and maintained greenway system provides a critical piece of New York City’s transportation infrastructure by safely linking communities and destinations and providing last-mile connections to transit stops (including bus, ferry, and subway).

How does the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway affect carbon emissions?

Even in transit-rich New York City, the transportation sector accounts for 30% of greenhouse gas emissions. Whether as a primary mode of transportation or as a first- and last-mile connection to transit, improvements to bike and pedestrian infrastructure have the potential to lower greenhouse gas emissions.

How can the results of the study support the advocacy of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway, as well as other greenways?

With 22 miles of the greenway in use, and the rest either under construction or committed to, the study seeks to quantify the many benefits of the Greenway to its many communities and to the city at large. Our hope is that this user study will be utilized to continue to improve the Greenway through wide travel lanes for different uses and speeds; for full protection through curbs and planting beds for safe separation from automobile traffic; and planted buffers to provide shade and cooling, beauty, habitat for wildlife, and stormwater capture; and for better wayfinding and identity.

We hope the results of this study will not only support the completion of the Greenway but also aid the construction of greenways across the city and beyond. It is also our hope that this study will be utilized for greenway planning initiatives described above, namely the creation of the citywide greenways plan; greenway design and equity standards developed through the USDOT RAISE grant; the Destination Greenways Program; and other design and construction efforts.

How can this study serve as a model for future studies?

In testing new methodologies made possible by emerging technologies and an innovative partnership, we intend this study to serve as a model for user studies of greenways and bike and pedestrian infrastructure writ large. To this end, we aim to be transparent about our successes and challenges in implementing such a novel approach.

While this project draws on many data sources, the project team collected data from three primary sources: Numina sensors, intercept surveys, and an online research panel survey. The three different sources allowed for insights not possible with any one source. By combining the datasets, we were able to combine data on volumes with qualitative data like trip purpose and demographic data. As with even the most robust datasets and data collection efforts, there are limitations which the project team took steps to mitigate. A more detailed methodology can be found here.

Numina Sensors

Numina sensors use machine learning to detect what type of object, whether a pedestrian, bicycle, truck, or car, is moving across their view, without storing any personal identifying information. The pathways of each pedestrian or vehicle are tracked across the view, allowing for more detailed data on how people are using the greenway, not just how many. For this study, all 32 Numina sensors were installed on light poles along the 29 mile greenway, collecting data for 14 months, between March 1, 2023 and April 30, 2024. Sensor locations were chosen to provide as much coverage of the greenway as possible, as well as incomplete sections of the greenway and off-greenway sites of interest, such as near transit or bridges. However, due to restrictions on which light poles were eligible to host sensors, there are several gaps in coverage, especially along the southern half of the greenway.

Intercept Surveys

Between June 2021 and September 2022, the project’s field research team collected over 1,000 intercept surveys at seven locations along the greenway. Surveys were collected at different times of day and days of the week. Greenway users were stopped and asked to answer a five minute survey, including questions regarding trip purpose, origin and destination, whether their trip had a connection to transit, and demographic information. The survey results were weighted based on nearby sensor counts based on whether the respondent was a pedestrian or cyclist, and the time of year.

Online Research Panel

In addition to the intercept surveys collected on the greenway itself, the project team used the online surveying service Qualtrics to survey 330 residents of the neighborhoods surrounding the greenway. Respondents were selected to accurately reflect the demographics of the neighborhoods surveyed. The online survey allowed for more detailed questions about general greenway use, as well as the opportunity to hear from greenway non-users.

Implementation challenges

Obtaining approval and permits from the New York City government for installing the sensors on street poles took over two years, far longer than anticipated. Negotiating with the electrical utility ConEdison over how to measure and bill the power also took several months. In addition, installation costs for the electrician proved much higher than was initially budgeted. While there were delays and added costs, they did not derail the project. Unfortunately, it did mean that data collection from the intercept and online surveys was not simultaneous with the Numina sensor data.

The project also faced several technical challenges, as expected with any cutting-edge technology like the Numina sensors. Due to the delays in getting approvals for sensor installation, survey collection was completed before the sensors were installed, instead of being simultaneous as intended. Sensor downtime, resulting from issues ranging from loss of power supply to software bugs to, in one case, a light pole being struck by a car, led to some gaps in the data. Loss of power to the sensors was the single biggest issue, as restoring power meant coordinating with DOT, Con Edison, and the electrician contractor to diagnose the problem and solve it, which proved to be too costly and time consuming. As a result, three of the 32 sensors were not functional during the data collection period, and an additional three were operational for only half the data collection period. Software issues were able to be resolved remotely, though some sensors still lost thousands of hours of data. Overall, however, 18 of the 32 sensors were able to collect data for at least 90% of the study period. Where possible, efforts were made to account for gaps in the data. Environmental factors such as camera obstructions and low lighting at night may also have some effect on data quality, but those issues are harder to detect, and therefore account for, in the data.

The Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway is a vital asset for surrounding communities and for Brooklyn. Our sensors counted an average high of 23,500 bicycles and 36,000 pedestrians per day using the Greenway during the peak month of July. Even during the least active month, January, we recorded a daily average of 7,400 cyclists and 16,500 pedestrians. For comparison, the NYC Ferry sees about 17,300 daily passengers, and the G Train, which serves several Brooklyn waterfront neighborhoods, has a daily ridership of around 160,000. We found that the majority of trips on the greenway use it for recreational purposes, though a substantial number of people use it for commuting. Nearly three quarters of Greenway users are on it at least a few times per week.

One Greenway, Many Uses

Greenways offer myriad benefits, not just to their surrounding communities, but to the city as a whole. From public health and quality of life, to job generation, carbon emissions reduction, and climate change adaptation–the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway offers all of these benefits, but different sections emphasize some benefits over others. Once completed, the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway will be a continuous 29-mile corridor, but it also has distinct segments that serve users in different ways. The spatial context and design features of the greenway, along with the usage data we collected, led us to identify eight segments, each with their own character, usage, and combination of benefits. Some, like the Williamsburg/Greenpoint segment, are integrated into the surrounding street grid and proximate to job centers, allowing for easy access and encouraging bike and pedestrian commuting. Others, like the Jamaica Bay Greenway segment, have limited access points, are located within parkland, and further from job centers, encouraging activities like long walks, runs, and bike rides for fun and exercise. Some segments are complete, others are in construction, and some are planned and incomplete. The demographics of the greenways neighborhoods also have many differences. To better understand how and why people use the greenway, it’s crucial to examine the similarities and differences between each of these segments.

Exercise, recreation, and space for community gathering

Exercise and recreation

Along every section of the Greenway, most people are using it for recreation, exercise, or meeting up with friends and family. Along the Shore Greenway and Jamaica Bay Greenway sections, the share is over 90%. Nearly half (48%) of Greenway users were headed to or from a park, and another 15% were simply doing a loop from their homes, implying that the greenway itself is the destination.

Greenways promote the public health of surrounding communities. (2013). An estimated 6,200-16,500 people use the greenway for exercise every day, and as many as 21,500 per day during warm weather months. Sections of the Greenway that run through parks are particularly popular for exercise. Nearly 9 out of 10 people using the Greenway for exercise report using it at least a few times per week.

Community gathering

The Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway is a vital space for gathering. 36% of greenway users are accompanied by friends or family. 6% of adult users are there with children, and 11% are walking a dog. In some locations, these groups are using the greenway to get to destinations like parks, beaches, restaurants, or shopping centers, and for others the greenway itself is the destination, as with Brooklyn Bridge Park, Shore Parkway Greenway, and the Jamaica Bay Greenway portions. The Greenway has created more opportunities for people to stay healthy, enjoy the city, and connect with friends and family. For folks using the greenway for recreation, 30% report that they would not have made the trip at all without the Greenway.

Demographics

Gender: Overall, Greenway users are equally likely to be men or women. However, women make up only about one third of bicyclists, similar to figures about the cycling gender gap in US cities. Several studies have investigated the gender gap in cycling and reasoning behind why such a disparity exists: Hosford and Winters (2019) found that 25.5% of Citi Bike users in 2018 were women ; In 2017, only 28.5% of bicycle commuters in New York City were women. Research suggests that women experience more cycling constraints and less positive attitudes towards biking than their male counterparts, which can be attributed to safety concerns, lack of biking infrastructure (e.g. bike racks, green spaces, off street routes), and a higher complexity in travel patterns due to “differing household and work roles.”

Race and ethnicity: For each section of the greenway, racial and ethnic demographics generally reflect the demographics of the surrounding communities, with some instances where representation of different races and ethnicities lands below or above the demographic make-up of neighborhoods adjacent to the greenway. For example, in the Williamsburg/Greenpoint section, census tracts within a half mile of the greenway are, for the most part, demographically comparable, except for residents of Asian or Pacific Islander (AAPI) descent who make up a larger percentage (8.2%) of greenway users on this segment compared to the 5.2% of AAPI residents living nearby. Along the Sunset Park section of the greenway, users are more likely to be White (53.6%) and less likely to be Hispanic/Latino (17.7%), while surrounding communities represent the inverse: 34.1% White and 38.6% Hispanic/Latino.

Income and education: One quarter of users declined to give their income, but greenway users who did were more likely to have incomes over $75,000 than the surrounding communities.

Safety

Overall around one quarter of greenway users indicated that they felt unsafe using the greenway, with a similar percentage of users either “somewhat agreeing” or “strongly agreeing” with at least one of the following statements:

“I worry about being hit by a motor vehicle while using the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway” (27%)

“I worry about my personal safety when using the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway (i.e. harassment, assault, etc.)” (28%)

“I worry about police harassment or discrimination while using the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway” (24%)

There was little difference in safety perceptions between male and female users, with male users only slightly more concerned about safety issues. This conclusion is an interesting contrast to a collection of research that indicates higher perceptions of safety risks and safety related concerns among women cyclists. Similarly, answers were relatively consistent across racial demographic groups as well. When answering the question, “How would you have made this trip without the greenway?” many respondents mentioned how important the safety the greenway provides is to them, even if they still would have biked or walked to their destination.

Cyclists were more likely to report encountering unfavorable conditions along the greenway (40%) than runners (36%) and walkers (27%).

Weather

One limitation of greenways is that they are exposed to the elements. As expected, poor weather–in the form of extreme cold, extreme heat, rain, snow, and even wildfire smoke–does reduce greenway usage. And yet, poor weather conditions only reduce greenway usage by about 30% for pedestrians, and 42% for cyclists. Portions of the Greenway in park settings are more affected than those on city streets. That most pedestrians and cyclists still use the greenway in poor weather demonstrates just how critical the greenway is for its users.

Car-free mobility and connection to transit

Carbon emissions

The BWG’s waterfront location gives its users access to NYC Ferry locations, from Greenpoint to Bay Ridge. Ferry connection was the highest reported type of transit connection along the Greenway, especially in Brooklyn Bridge Park, Red Hook, and especially in Sunset Park, where nearly 20% of users were connecting to the ferry. Subway connections were most common along parts of the greenway in close proximity to subway stations.

Nearly one third of respondents to the online survey reported that mass transit is the way they most frequently get to the greenway, nearly as many who walk.

In some cases, greenway users traveled to or from the BWG by car. This was highest in areas where the BWG travels through a park, such as Brooklyn Bridge Park, Shore Parkway Greenway, and the Jamaica Bay Greenway. With the exception of Brooklyn Bridge Park, car travel to the greenway is correlated with neighborhoods where car access is higher. According to online survey respondents, 17% reported that they typically drive to the greenway.

Case studies of other greenways have shown positive associations between greenways and fewer vehicle miles traveled. A study conducted on the Comox-Helmcken Greenway in Vancouver, BC found that participants living in close proximity to the greenway route displayed a 22.9% decrease in greenhouse gas emissions from motorized vehicle use, compared to residents living further away whose GHG emissions increased by over 40%, indicating a positive environmental impact when residents had the option to use the greenway for mobility instead of a car.

The “green” character of greenways also plays a role in reducing carbon emissions, as the trees and plants surrounding many parts of the greenway absorbs CO2.

Commuting

New York City’s share of bike commuters has increased at twice the rate of other US cities over the last decade and a half. More than 23% of BWG bike trips and 12% of all BWG trips are for commuting, which represents an estimated 3,000-7,000 people per day during the spring and summer. Commuting is much more common on sections of the greenway near job centers, like Williamsburg/Greenpoint (22%), Brooklyn Bridge Park (19%), and Red Hook (19%). According to our survey data, if the BWG were not there, nearly 40% of commuters would not have biked or walked to work that day. Over 85% of BWG commuters also report using the greenway either every day or a few times per week. BWG commuters were less likely to be aware that they were using the BWG than other users.

23% of trips on the greenway are to or from, or have a stop at, commercial destinations such as stores, restaurants, or hotels, and along certain sections like Brooklyn Bridge Park and Red Hook/Columbia St, that figure is around 30%.

E-bike usage has surged across the city in the last several years, leading to debates on topics ranging from safety to equity to e-commerce. Unfortunately, this project was not able to capture much meaningful data regarding e-bike usage on the Greenway. Just 4% of cyclists intercepted for surveys were using an e-bike, which we believe to be an undercount. We hope to conduct more research on e-bike usage in the future.

Ecological corridors and green infrastructure

In addition to helping mitigate climate change, Greenways play a critical role in making cities better adapted to climate change, as well as more ecologically sustainable. The BWG links together parks along its planned route, creating a green corridor from Greenpoint to Howard Beach. Building greenways can be an opportunity to implement green infrastructure like rain gardens and bioswales, as RPA’s 2022 Re-envisioning the Right of Way report highlighted. These benefits have more to do with the design and implementation of greenways rather than their users, and so are beyond the scope of this study.

Greenway Improvements

Greenway Gaps

Counting users along the entire length of the greenway allows us to compare complete and incomplete sections of the greenway. In general, fewer cyclists were counted along portions of the greenway route that have not yet been completed.

Awareness

Only around 3/5ths of greenway users were aware they were using the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway when surveyed, with not much difference between different areas. Bicyclists are more likely to be aware of the greenway than pedestrians. Brooklyn residents living near the greenway surveyed in the online panel were shown a map of the BWG and asked if they had ever visited the greenway. 55% reported that they had, and an additional 7% responded “maybe.”

Nearly 60% of respondents to the online panel survey who had not used the greenway reported that they have not visited the BWG because they did not know where it is. Additional answers included that the greenway was not accessible, that they did not have access to a bike, or that it was too far away or not convenient.

Overview

The following section details the different segments of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway: the types of land use and infrastructural development throughout the many neighborhoods that line the waterfront trail, major destination sites for Brooklyn visitors and residents, and the arterial system of bike routes and mass transit lines that connect the BWG to more central parts of the borough and New York City at large. This section of the user study follows a descriptive path between the northernmost and southernmost parts of the Brooklyn waterfront, with insights into how people interact with and use the different segments of the Greenway, based on our data collection and field notes, in order to provide a glimpse into the dynamic character and varying nature of one of Brooklyn’s highly frequented public amenities.

Williamsburg/Greenpoint Segment

The northern segment of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway is one of the busiest for both pedestrians and bicyclists. The areas of Williamsburg and Greenpoint along this section of the greenway have experienced major residential development over the last 20 years, along with new parks and commercial destinations. The greenway runs alongside city streets here, primarily West Street and Kent Avenue, serving as a major north-south bike route and connecting with several east-west bike routes.

The northern end of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway begins on Commercial Street, just a block away from the Pulaski Bridge entrance over Newtown Creek where travelers have a direct route to Long Island City and further connection to Midtown Manhattan. It then runs along West Street, past many new residential developments and a handful of shops and restaurants. This segment runs only a couple blocks from the G train, and greenway users can choose to connect to the Greenpoint ferry landing nearby, which is adjacent to Greenpoint Public Park on India Street.

Across the Bushwick Inlet, the greenway path in Williamsburg stretches down Kent Ave and through a corridor lined with new residential and commercial developments like large apartment buildings and stores. This part of Brooklyn is a major hub for social activities among New Yorkers and out of city visitors as it hosts recreational destinations like Marsha P. Johnson Park and Domino Park. The many bars and restaurants close to the greenway are also a draw for residents and visitors.

The neighborhood also hosts the Brooklyn side of the Williamsburg Bridge, a major artery connecting users to Manhattan’s central business district. This section of the greenway is well connected to other forms of transit, like the L, J/Z, and M lines and the North/South Williamsburg Ferry stops. Around 10% of greenway users transfer to or from the subway, and an additional 7% connect to other modes like ferry and bus.

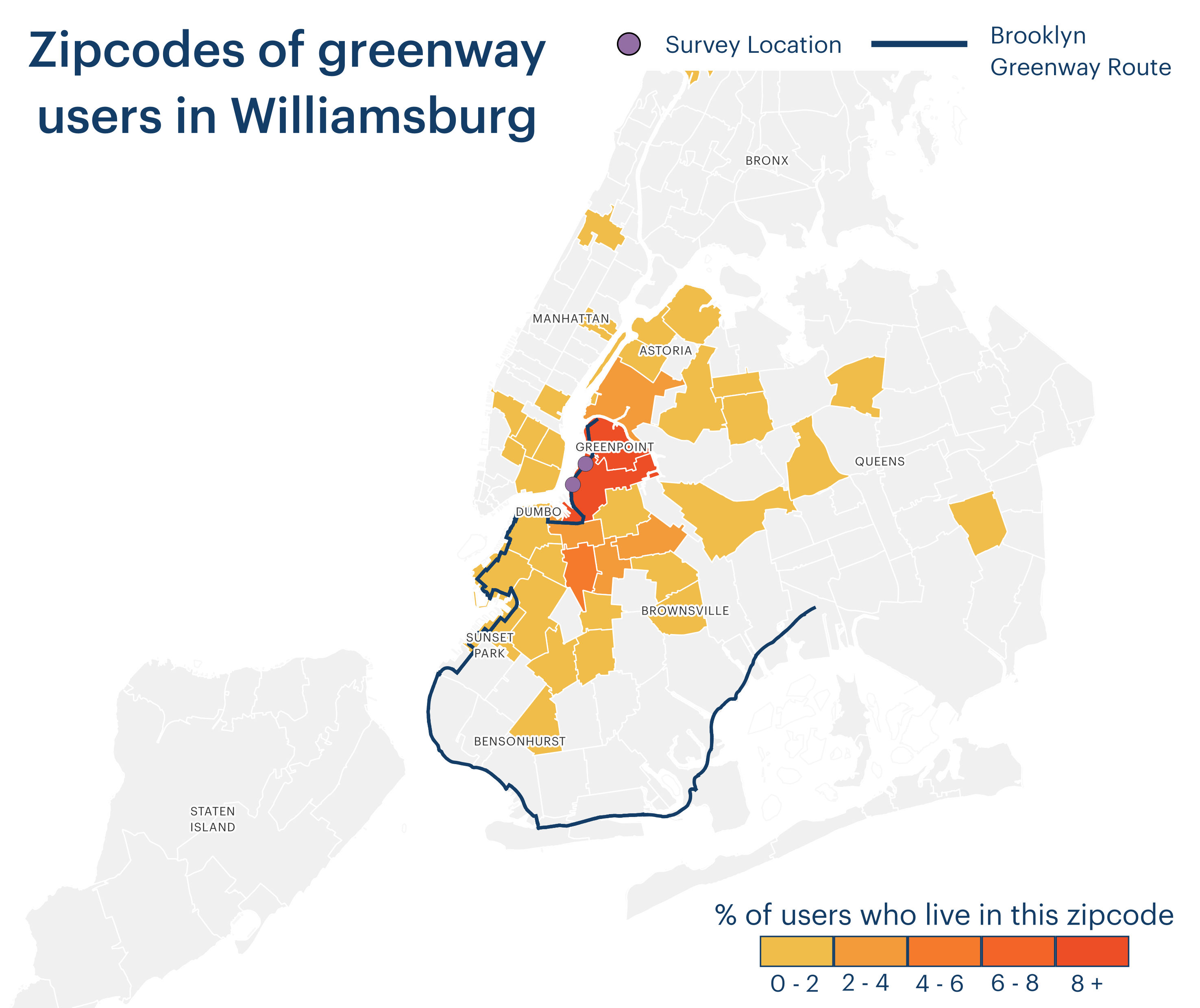

26% of users on this section of the greenway reported living in zip codes in and near Williamsburg and Greenpoint. Around 8% of users of this section came from other boroughs.

This section of the greenway has some of the highest daily average counts of both bikers and pedestrians, peaking at nearly 7,900 daily users in May.

Greenway Use and Trends in Williamsburg/Greenpoint

Greenway users in the Williamsburg/Greenpoint section of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway who were surveyed at two different locations on Kent Avenue about their home zip code reported a series of different neighborhoods throughout four of the five boroughs. While most users reported living in Brooklyn neighborhoods like Clinton Hill, Bushwick and Bed Stuy, there were also people living in the Bronx, Queens, and Manhattan who traveled to the northern section of the greenway.

Both pedestrian and bicycle counts in Williamsburg/Greenpoint peak at primary commuting hours during the weekday: around 8 am in the morning and 5-6 pm in the evening. On weekends, pedestrian and bicycle traffic are highest during mid-day: noon to 2 pm.

Most users on the Williamsburg/Greenpoint section reported using the greenway to exercise or partake in other forms of recreation. This segment of the greenway sees a higher percentage of commuters than other segments. Cyclists tend to use the greenway more for non-recreational uses compared to pedestrians: 37% of cyclists are running errands and commuting to work. Of the 16% of users that are connecting to transit, the majority specified intentions to use the subway.

Temporary markings on the bike path on the Brooklyn Greenway in Greenpoint

Brooklyn Navy Yard/DUMBO Segment

Much like the previous segment, the section of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway that runs alongside the Brooklyn Navy Yard and through DUMBO (once completed) is one of the most heavily used. Flushing Avenue in particular is a major bike artery, connecting Downtown Brooklyn not only with Williamsburg through the previously described segment of the greenway, but with neighborhoods like Bedford-Stuyvesant, Clinton Hill, and Fort Greene via several north-south bike route connections. This part of the greenway is primarily industrial and commercial. The Navy Yard has experienced major new industrial development, while DUMBO has had an office boom, leading to a major growth in jobs in close proximity to the greenway. Unfortunately no survey data was collected from this segment of the greenway, so our insights are limited to data captured by the sensors.

Users begin their journey on this segment by biking next to the lush, open space of the Naval Cemetery Landscape, a historic Naval Hospital burial ground that has since been revitalized as a public amenity, making it a popular destination and bike path for greenway users. This section of the greenway on Williamsburg Street is lined with trees and protective barriers that separate bikers and pedestrians from parallel vehicle traffic. Turning right onto Flushing Avenue, the greenway is separated from other road traffic by a street median, allowing bikers and pedestrians distinct lanes in the two-way traffic street. The waterfront takes on a combined industrial and commercial feel here with the Navy Yard’s old shipping piers, ferry terminal, and small number of business spaces, like Newlab and Steiner Studios, lining one side of the greenway path. Flushing Avenue on the southeastern side is also lined with old brick buildings, newer residential developments, parking lots and varying storefronts.

Though daily average pedestrian and bicyclist counts are somewhat similar during cooler months in the Navy Yard/DUMBO section of the greenway, the warm months between May and August display far more bikers in this part of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway. Similar to the greenway in Williamsburg and Greenpoint, the route along the Navy Yard and DUMBO neighborhoods are also high in traffic.

Weekend and weekday use on the Navy Yard/DUMBO greenway segment is similar to the Williamsburg/Greenpoint section, with weekday peaks at morning and evening commuting hours for both bicyclists and pedestrians.

Brooklyn Bridge Park Segment

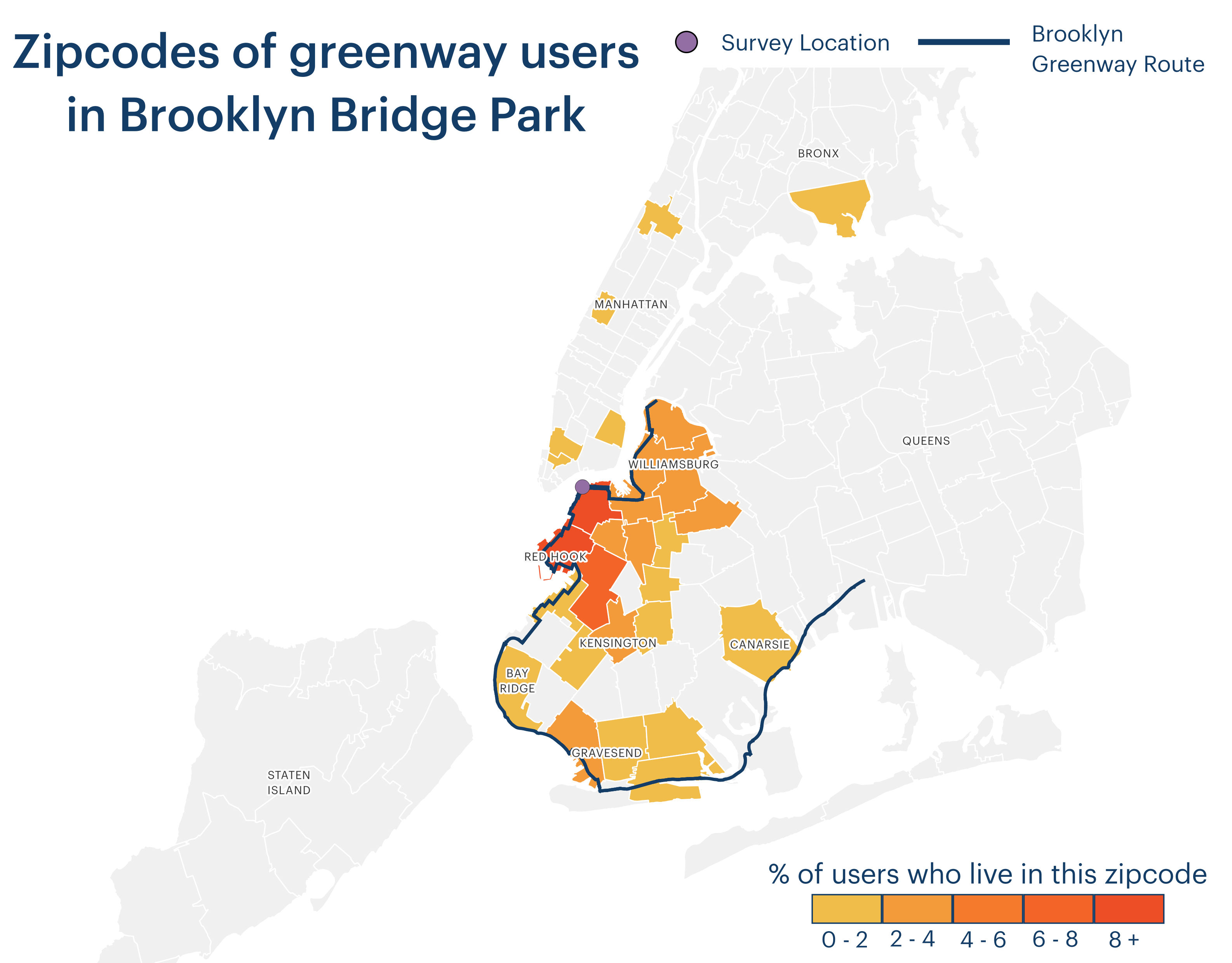

This section of the greenway is entirely within Brooklyn Bridge Park, a popular destination in itself, and is entirely separated from motor vehicle traffic. Opened in 2010, Brooklyn Bridge Park features several piers with a diversity of outdoor recreational programming, all connected by the greenway. Access to this section is largely limited to the northern and southern ends of the park. This section of the Greenway is also close to the Brooklyn Bridge, DUMBO, and many restaurants and shops, and is popular with tourists and city residents alike. Indeed, the Brooklyn Bridge Park section of the greenway has the most tourists of any section, as well as a higher percentage of users from further away. Just over half of Greenway users in the park are local residents from adjacent zip codes. Greenway users here were also most likely to be with friends or family (41%) compared to other sections.

The greenway here is close to two ferry stops at opposite ends of the park: DUMBO landing and Brooklyn Bridge Park Pier 6. It’s also an 8 minute bike ride from several subway stations making it a conveniently transit oriented destination for greenway users. This section of the Greenway has the highest percentage of users connecting to transit, with 17% connecting to the ferry and 11% connecting to the subway. Brooklyn Bridge Park’s greenway section also borders Brooklyn Heights, a largely affluent and residential neighborhood close to Downtown Brooklyn. This section of the greenway where Atlantic Avenue intersects Columbia Street.

Following the painted green lanes on Navy Street north into DUMBO, the greenway here is similar in feel to Williamsburg with its mix of commercial and residential uses, greenway users pass by a large grocery retail complex and NYCHA’s Farragut Houses Community Center as they make their way closer to the waterfront. DUMBO is also a big office district and has major transit connections like the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges, in addition to three subway lines, making the greenway here a prime location for commuters moving between Manhattan and Brooklyn. While the greenway section retains this commercial and residential development along parts of Water and Front Streets, where the greenway is still incomplete, it breaks into more green and open space beyond the Manhattan Bridge overpass, with Brooklyn Bridge Park’s recreational areas like Main Street Park and Empire Fulton Ferry. These green gathering points, which sit on either side of the Manhattan Bridge provide some recreational relief from DUMBO’s bustling commercial and touristic center.

Bike path near the Brooklyn Navy Yard — Here the bike path is a grade separated path integrated with street grid

Greenway Use and Trends near the Brooklyn Bridge Park

Daily average traffic along the Brooklyn Bridge Park route is similar to counts along the Williamsburg/Greenpoint section of the greenway, with combined counts peaking at 5,505 users in July. Notably, pedestrian counts on the Brooklyn Bridge Park section are significantly higher than bicycle counts during all months of the year and, interestingly, up to eight times higher during the colder months of December and February.

The lowest use for both cyclists and pedestrians during primary weekday hours is at 10am. Given that use on weekday mornings peaks around 8am for both modes, it can be inferred that pedestrians and bikers are commuting during this time on weekdays. Additionally, more than 10% of cyclists are on the greenway around 5 pm, indicating that more users are biking from work rather than traveling by foot. For pedestrians and cyclists alike, weekend use is higher during the late morning to afternoon hours between 10 am and 3 pm.

While most pedestrians and cyclists are on the greenway for exercise and other recreational activities, a notable amount of cyclists also use the greenway to commute (28%) compared to pedestrians (5.3%).

Red Hook / Columbia Street Segment

The section of the Greenway that runs through the Columbia Street Waterfront District and Red Hook is partially complete. The protected portion of the greenway runs primarily along Columbia, Van Brunt, and Imlay Streets, with another segment along the Erie Basin Park Promenade. The remainder of the route through Red Hook is a mix of regular bike lanes, sharrows, and a few blocks with no bike lanes at all.

Greenway users biking along the complete, painted, and protected greenway section on Columbia Street pass by the Brooklyn Marine Terminal (formerly Red Hook Container Terminal), a 122 acre waterfront industrial space that encompasses Pier 7 through Pier 12. The Columbia Street Waterfront District and Red Hook are both historically home to commercial waterfronts that continue to host factories, businesses, and large lots for manufacturing, commercial and transportation uses.

Given the largely industrial use of the waterfront in these two neighborhoods, there is limited access to coastal recreational activities, unless residents are looking to take the NYC Ferry at the Red Hook/Atlantic Basin stop across the channel to Governor’s Island. Users can also journey further south on Conover Street along the incomplete section of the greenway in Red Hook for a different experience: the southern end of the Red Hook waterfront down by the Gowanus Bay is partially reminiscent of a sea-side village with a handful of restaurants, breweries, and smaller green spaces. Red Hook is home to a collection of small arts and cultural spaces like museums and galleries, as well as IKEA. Many of these attractions sit close to the waterfront, making them easily accessible from the bike path or a nearby ferry stop. 16% of users in this section are connecting to a ferry, and 5% to the subway, despite the nearest subway station being at least a 10 minute bike ride.

Columbia Street and Red Hook also house an array of multi-family residential developments along the greenway and further inland. NYCHA’s Red Hook Houses, the second biggest public housing complex in the country, sits in the central part of Red Hook, just a few minutes’ walk from the greenway route.

Greenway Use and Trends in Red Hook/Columbia Street Waterfront District

Greenway users along the Red Hook/Columbia Street Waterfront District section of the greenway were surveyed about their home zip codes at two different locations along the greenway route: the corner of Pioneer and Conover Streets as well as the intersection at Beard Street and Dwight Street. Survey results found that over three quarters of users had home zip codes in Brooklyn, with some Red Hook/Columbia Street visitors living in Lower Manhattan, Queens, and South-Central Bronx.

Most Brooklyn based greenway users along this section live in Red Hook and adjacent neighborhoods along the waterfront, with a small number of South Brooklyn residents traveling up to spend time on the route. 11% of greenway users in this section live in other boroughs.

Daily average bike and pedestrian counts along the Red Hook/Columbia Street section are somewhat lower than traffic counts in more northern sections of the greenway–combined bicycle and pedestrian counts peak in May at 1586 users.

Most cyclists tend to use the greenway later in the day on weekends between noon and 4 pm. Weekday cycling rises to 6% around 8 am and 10% around 5 pm, indicating that more people are biking later in the day during Monday-Friday. Pedestrian use of the greenway peaks in the morning on weekdays, but weekend users who are walking or running on the greenway are most frequent in the late morning between 10am and noon.

Users on the greenway for recreation, exercise, commuting, and running errands are pretty comparable between both bikers and pedestrians on the Red Hook/Columbia Street greenway, with a larger percentage of pedestrians confirming intentions to meet up with family and friends. This section also has the highest number of pedestrian commuters (16.4%) compared to other parts of the greenway.

Sunset Park Segment

Users start on the Sunset Park greenway at the corner of Smith Street and Hamilton Avenue and follow the route adjacent to the Gowanus Expressway. The beginning of the waterfront greenway here is incomplete, quite industrial in character, and can be dangerous to bike along as it is unmarked and close to street traffic. This incomplete segment also follows 29th Street up into 2nd Avenue and runs along the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal (SBMT), a historically vacant and industrial section of the waterfront.

SBMT is also a three minute walk away from the bustling commercial section of Industry City, where users can traverse along brick lined streets to nearby shops, restaurants, and office buildings and even connect to the N/R/W subway line along 4th Avenue. Sunset Park, which has a majority Latino and Chinese population, also hosts a mix of single and multi-family residential development.

As the route extends further north from 1st Avenue and 43rd Street to Bush Plaza, closest to the waterfront, it becomes more green along Bush Terminal Park. The greenway here is complete, separate from street traffic and runs, clearly marked with signage, along the grassiest part of the Sunset Park waterfront. Users biking in Bush Terminal Park have access to benches, small lawns, and walking paths for recreational activities. There is also the nearby Socceroof complex that users can easily reach from the greenway.

The end of the Sunset Park greenway section, at the corner of Shore Road and Colonial Road, is also near the Brooklyn Army Terminal, down the road from Owl’s Head Park. Though the end of the path here is a block away from Brooklyn’s Belt Parkway, the route is marked, separated from car traffic with a street median and users can even connect to the NYC Ferry transit near Pier 4. The South Brooklyn Marine Terminal and Brooklyn Army Terminal have been partially underused for many years; but recent investments in the neighborhood’s quiet waterfront intend to bring a new offshore wind industry to Sunset Park with wind farm manufacturing and operations activities.

The Brooklyn Greenway in Red Hook

Greenway Use and Trends in Sunset Park

Users in Sunset Park and its vicinity were surveyed at three different locations on and near the greenway route: 2nd Avenue and 58th Street, 4th Avenue and 59th Street, and near Owl’s Head Park at Colonial Road and 67th Street. Similar to other sections of the greenway, most users reported living in surrounding Brooklyn neighborhoods with a small percentage traveling from Manhattan, Queens, and Staten Island.

The completed section of the greenway in Sunset Park along 2nd Avenue was one of the newest at the time of data collection, which may explain the relatively low volume of users. Users in Sunset Park are more likely to be walking than biking during all months of the year.

Bicyclists peak in weekday use around 5 pm and seem to also be frequently using the greenway quite early in the morning around 7 am, most likely using the greenway to commute to and from work. Similarly, pedestrian use during 8 am and 5 pm on weekdays is quite high, although peak pedestrian traffic on the Sunset Park greenway occurs around 4 pm during the weekend.

The majority of users are on the greenway for exercise or recreation, with a higher number of cyclists using the greenway to commute (18.8%) compared to pedestrians (10.2%). Similar to Red Hook/Columbia Street users, we see most transit connections happening by ferry on this section of the greenway.

Shore Parkway Greenway Segment

The fully complete Shore Parkway Greenway borders the residential neighborhoods of Bay Ridge and Bath Beach with large parks and green spaces for recreation along the waterfront. Users begin their trip here at the Colonial Road entrance of Owl’s Head Park, a major destination point for Greenway users and Brooklyn residents. The path runs along the Owl’s Head Park Dog Run, close to the Bay Ridge Ferry stop, before breaking out onto a separated and clearly marked path with an unobstructed view of the New York Bay. Due to the large Belt Parkway throughway running between the waterfront greenway route and residential streets of the two adjacent neighborhoods, there are limited access points from the greenway to Shore Road and areas further inland. The Shore Parkway Greenway ends at the Southeastern corner of Bensonhurst Park, at the Bay/Shore Parkway intersection right before the freeway overpass.

Bay Ridge and Bath Beach are largely residential and both host smaller one and two family housing developments further inland. The R subway line that runs down 4th Avenue in Bay Ridge and D train on 86th Street in Bath Beach provide some public transit mobility from these less densely developed neighborhoods into the more commercial centers of New York City. Given the Shore Greenway’s largely recreational waterfront and limited train line options with mass transit, users are less likely to be commuting along this section of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway.

In this area, pedestrians are more likely to use the route, with up to nine times more pedestrians than cyclists on the route during winter months and four times more in the summer.

Weekday and weekend use are similar between cyclists and pedestrians using the Shore Greenway, with midday being the most popular time for all modes during all days of the week.

Grade and landscape separated bike lane in Sunset Park

Over three quarters of bicyclists and half of pedestrians are on the Shore Greenway for exercise, with pedestrians also using the greenway for recreational purposes. A small percentage (10.4%) of users are on the Shore Greenway for commuting purposes. Pedestrians also reported using the greenway to meet up with friends and family. While 87.4% of Shore Greenway users indicated that they would not be connecting to mass transit, those who did were most likely to connect to the bus.

Coney Island/Sheepshead Bay Segment

The southernmost part of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway travels through several waterfront neighborhoods all varying from quiet and green to busy and commercial. These neighborhoods also host significant ethnic diversity: Gravesend and Sheepshead Bay both have prominent Asian communities, Brighton Beach is mostly White, and Coney Island has a large population of Black and Latino residents. Beginning in Gravesend, users journey adjacent to the Shore Parkway on a painted green and protected path past a series of large shopping plazas, parking lots, and even an amusement park. The greenway here also runs outside of Calvert Vaux Park, a public recreational area that features large fields and sports complexes.

As users travel down into the Coney Island and Brighton Beach neighborhoods, where the greenway route stretching along Neptune Avenue is planned but not yet complete, they are surrounded by large commercial developments, auto shops, and a sprinkling of commercial destinations, like restaurants and stores. This section on Neptune Avenue is just a ten minute walk and five minute bike ride away from the Riegelmann boardwalk and four miles of sandy coastline, making it a popular social gathering place for tourists and New York residents alike. The greenway here also has three subway stations nearby, like the Neptune Avenue F station and Ocean Parkway Q station that provide connections into Northern Brooklyn and Manhattan’s central business district.

Given their proximity to New York’s Lower Bay and orientation facing an opening to the Atlantic Ocean, Coney Island and Brighton Beach have a dense development of commercial buildings with more recreational uses along the coast. There is a variety of residential development in these neighborhoods: some private one, two, and multi-family developments in Brighton Beach and several public housing complexes on the western end of Coney Island.

The remaining part of this greenway section, which is fully complete, crosses on to Emmons Ave in the Sheepshead Bay neighborhood and travels along a small inlet, ending at the northwest corner of Lew Fidler Park. This final section of the Coney Island/Sheepshead Bay route is bordered by a series of wooden piers and waterfront seating on the south side. Users also pass small cafes and restaurants as they make their way through the neighborhood and closer to the Jamaica Bay Greenway.

Parking protected bike lanes in Sheepshead Bay

Greenway Use and Trends in Coney Island/Sheepshead Bay

Due to a combination of issues, the project team was not able to collect enough survey or sensor data to present trends for this section of the greenway. This section had few eligible light poles for sensor placement, and the two that were placed suffered technical challenges. In addition, we were not able to collect enough survey responses for this area.

Jamaica Bay Greenway Segment

The Jamaica Bay section of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway, which is fully complete, begins at the corner of Brigham Street and Emmons Ave and parallels the Belt/Shore Parkway all the way into the Howard Beach neighborhood. This part of the greenway is also coterminous with the other, separately labeled “Jamaica Bay Greenway.” Along this marked and sectioned off route, users travel along large green and recreational use destinations, with small pockets of sandy shoreline along the coast. Some of these larger waterfront green spaces include Floyd Bennett Field, Canarsie Park, and Shirley Chisholm Park. A short bike trip beyond either Floyd Bennett or Shirley Chisholm also leads to the Rockaways in Queens, an area frequented by residents and visitors during warmer months. This section of the greenway is home to 288 acres of wetlands and a public access Wildlife Refuge that welcomes visitors for activities like boating and bird watching.

The Jamaica Bay Greenway runs along the waterfront of a series of low density, residential neighborhoods with primarily one and two family housing developments. Canarsie and East New York specifically, whose waterfronts comprise roughly half of the greenway path, also have a majority Black population of residents. There are limited connections to rail in this easternmost section of Brooklyn, with a single L Station in Canarsie and the A train line which grants rail access to the nearby JFK airport. Given the limited mass transit options in easternmost Brooklyn, residents in these neighborhoods tend to rely on car use for mobility throughout the city compared to residents in other neighborhoods along the greenway.

The majority of Jamaica Bay Greenway users come from adjacent neighborhoods like Canarsie, Bergen Beach, Mill Basin, and Marine Park, with many other users traveling from other parts of Eastern Brooklyn. There are a small number of people living in Astoria (1.3%), Southern Queens (6.1%), and on Staten Island (0.7%) who also traveled to use the Jamaica Bay Greenway.

Overall use of the Jamaica Bay Greenway is lower compared to most sections. As a park trail with limited access points, it’s more popular with cyclists than pedestrians.

Greenway Use and Trends along the Shore Greenway

The vast majority of Shore Parkway Greenway users, who were surveyed on Shore Road near 4th Avenue, reported zip codes in South Brooklyn neighborhoods like Bay Ridge, Sunset Park, Bath Beach, and Dyker Heights. This segment had fewer users living in other boroughs or from distant parts of Brooklyn than most others.

Greenway Use and Trends along the Jamaica Bay Greenway

Users on the Jamaica Bay Greenway were surveyed at Canarsie Veteran’s Circle near the pier entrance about their home zip codes.

The majority of users are on the Jamaica Bay Greenway for exercise or other forms of recreation. 6.3% of cyclists did indicate that they are using the greenway to commute. Only 2.2% of users on this section reported that they were connecting to transit and of this percentage, the least of any section of the greenway.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Conclusion

With tens of thousands of daily users, the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway serves an important role for its communities, rain or shine. As a place for recreation, exercise, and gathering, as a corridor for commuting and connecting to transit, the Greenway promotes quality of life, public health, and sustainable transportation.

The considerable data collected and presented here represents a new model of understanding and measuring the impact of greenways on both users and the neighborhoods they run through. Newer technology like Numina sensors, combined with field research allow us to understand not only the role of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway, but also how people use it and how to improve it.

Recommendations

Complete the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway in the immediate short term

Study data shows a clear drop-off in usage of the aspirational BWG route in sections that are not complete (paint-only bike lanes, sharrows, or no bicycle facilities at all). NYC government has taken two different approaches to implementation — in some sections, like Kent Avenue in Williamsburg, the City established first phase greenway facilities using temporary materials in quick-build projects, resulting in high usage. In other areas, the City has elected to skip entry-level facilities and go straight to capital projects. Usage is high when completed, but takes decades to realize the benefits (the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway Implementation Plan was published by NYC DOT in 2012; significant stretches in Red Hook and Sunset Park are still awaiting capital construction kickoff). This data strongly suggests that the phased approach with entry-level facilities is the more beneficial approach — the City should seek to complete the remaining eight miles with temporary materials by 2025.

Follow through on the commitment to upgrade entry-level facilities

Once usable facilities are opened, NYC government can’t rest on its laurels and allow policy inertia to stall projects in their entry-level phase, as usage will increase to fill and exceed entry-level capacity. The City should follow through on the rest of the phased approach to create landscaped, grade-separated pathways with ample space for pedestrian and bicycle users — preferably on itineraries that are measured in smaller units time than generations, which is the case now. In particular, as the City moves forward with implementation plans across the other boroughs, it needs to maintain credibility with communities across the city that its phased approach will result in critical green open space infrastructure by following through on its earliest commitments along the BWG.

Prioritize the establishment of greenway-like alternatives around work zones

Similar to the need for greenways to be complete in the short term with entry-level, temporary facilities, and in the sense that repair and long-term reconstruction of greenways creates temporary breaks and incomplete sections, NYC government should strive to apply the spirit of Local Law 124 of 2019 — temporary protected bike lanes around work zones — to greenway construction as well.

Improve design standards to meet tomorrow’s usage needs and prevent vehicle intrusion

Greenway usage in 2023-24 in northern Brooklyn segments like Kent and Flushing Avenues exceeds expectations from 2010, when the projects that resulted in the BWG around the Brooklyn Navy Yard perimeter were designed. If it was designed with today’s usage in mind, the bike path likely would be wider, and the Flushing Avenue sidewalk would not have been narrowed. It would be best to adopt a future-proof mindset when designing capital projects. Additionally, greenway usage on West Street is notably lower than adjacent sections. The BWG on West Street makes use of a “mountable curb” design, which allows and encourages vehicle intrusion and parking. This issue is seen in other areas of NYC, including the Rockaways and Grand Concourse in the Bronx. Removing substandard designs from the toolkit, and remediating the ones already in use, would reduce vehicle intrusion and boost greenway usage.

Improve and standardize wayfinding for greenways

In the study, a considerable number of residents near the BWG reported not knowing where the greenway was, and there are also challenges to following the route. NYC DOT and NYC Parks have developed a recognizable greenway “medallion” sign, although its usage is inconsistent - both in terms of its appearance (sometimes appearing as a standard road sign, and sometimes appearing as a “pill”) and frequency of use (turns are inconsistently marked).

One example to follow could be from the NYS Empire State Trail program, which uses a standard road sign with turns (including straight-thrus) at frequent points, and full trail maps at major points. The Province of Quebec also has a similar wayfinding system, which differentiates its “Routes Vert” with a numbering system — since NYC DOT and NYC Parks use the same medallion for all greenways, additional information that clearly indicates greenway name and direction would be helpful.

Upgrade connections to surrounding neighborhoods and increase the number of access points

Greenway usage was considerably lower in southern Brooklyn sections than in northern Brooklyn. There can be a number of driving factors - proximity to job centers in northern Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Long Island City, proximity of businesses to the greenway, etc. One notable aspect is that the design of the BWG in northern Brooklyn has points to enter and exit the greenway at nearly every block, while the urban trail form of the southern Brooklyn sections are miles apart — excellent for recreational purposes, but not as optimized for work trips and non-recreational personal trips. Upgrading connections from surrounding neighborhoods to the greenway for pedestrians, runners, and cyclists should be prioritized throughout the corridor.

Maximize connections to public transportation

Greenway users have reported in the abstract that their trips are multi-modal. Intercept survey data indicates that in practice, this happens on a small number of trips, but that rate increases where public transportation is available — usually around ferry landings, as one would expect for a waterfront greenway. The City should strive to make sure it is optimizing connections for ferry, bus, and subway users.

Appendix

Acknowledgements

Authored by

-

Hunter Armstrong

Brooklyn Greenway Initiative, Executive Director

-

Brian Hedden

Brooklyn Greenway Initiative, Advocacy & Greenway Projects Coordinator

Project Team

Brooklyn Greenway Initiative

Hunter Armstrong, Brian Hedden

Regional Plan Association

Ellis Calvin, Ravena Pernanand, Rob Freudenberg

Numina

Tara Pham, Can Sucuoglu

New York City Department of Transportation

Shawn Macias, Carl Sundstrom

Special thanks to:

Richard Mai, Terri Carta, Anne Krassner, Sam Bowden Akbari, Srajan Bhagat, Elisabeth Kalomeris, Julia Ehrman, Remy Schwartz, Dave Zackin, Meaghan McElroy, Roland Lewis, Ted Wright, Jessica Bressman, Angel Geronimo, Carlos Mandeville, Sherice Avant, Margaux Groux, Paula Rubira

Field Research Team:

Jack Darcey, Wisely Chang Wu, Jacob Boersma, Daniel Flores, Daniel Kim, Max Murgio, Matthew Shore, Joaquim Stevenson-Rodriguez, Greg Suter, Maribel Tale, Eric Thompson, Jess Wachtler, Jade White

Technical Advisory Committee:

Office of the Mayor of New York City: Aaron Charlop-Powers, Sonia Guior; Brooklyn Bridge President’s Office: Brit Byrd; NYC Department of City Planning: Benjamin Huff; NYC Economic Development Corporation: Lena Ferguson, Megan Quirk; NYC Department of Parks and Recreation: Maya Dutta, Mitchel Loring, Sarah Neilson, Zoe Piccolo; NYC Transit: Chandler Diffee; City University of New York: Alison Cosgrove; USDA Forest Service: Erika Svendsen; Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation: Tracey Capers, Sarah Wolf; BetaNYC: Noel Hidalgo, Zhi He; Brooklyn Bridge Park Corporation: Eliza Perkins; Brooklyn Greenway Initiative (board members): Rich Miller, Tiffany Stone; Lyft (Citibike): Thomas DeVito, Laura Fox, Inbar Kishoni, Patrick Knoth; Con Edison: Kate Mammolito, Justin Hohn; Oonee: Shabazz Stuart; National Parks Conservation Association: Lauren Cosgrove; Street Plans: Michael Lydon; The Brown Bike Girl: Courtney Williams; Individual Members*: Samuel Frommer; Justin Ginsburgh; Jacqueline Lu; Elizabeth Weiland

*Participating not-affiliated with a company or organization.

Funders:

This project was made possible with generous support from New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, and from the Altman Foundation, New York Community Trust, Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, and Achelis and Bodman Foundation. Additional support was provided by Two Trees Management Company, Industry City, and Hyde and Watson Foundation, as well as former NYC Councilmember Brad Lander, Cumberland Packing, Bernard & Anne Spitzer Charitable Trust, Con Edison, Park Tower Group, HR&A Advisors, HK Organization, and Douglaston Development.

Related Reports

532